South Africa is the world’s seventh-largest coal producer and its sixth-largest consumer. Although only one-third of the country’s coal is exported (45% of it to India), overseas sales achieve a higher price than domestic sales and earn about 45% of industry’s total revenue. According to the Minerals Council South Africa (MCSA), in 2016, domestic coal sales of 181.4 million tons (Mt) were valued at ZAR61.5 billion, and exports (68.9 Mt) were worth ZAR50.5 billion. ‘Coal has played and continues to play a major role in the South African economy, with its impact spanning the entire value chain – from production to beneficiation,’ Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr directors Jackwell Feris and Rishaban Moodley state on the firm’s website. ‘Compared to all other commodities, coal was the largest revenue generator for the South African economy during 2017.’

However, like most countries, South Africa has pledged to cut its use of coal in terms of the 2015 Paris Accord on greenhouse gas emissions. The World Bank attempted to stop funding for coal-burning power stations as long ago as 2010. In September it was reported, albeit unconfirmed, that one of South Africa’s ‘big four’ banks, Standard Bank, had told the Department of Energy that it could no longer finance the construction of new coal-burning power stations. Among its international peers that have taken the same stand are Standard Chartered, HSBC, Societe Generale and Deutsche Bank. It is notable that only one of the four future scenarios painted by the MCSA’s 2018 National Coal Strategy suggests an increase in the growth of demand for coal around the world. The scenario, which depicts a 5% increase in demand for coal, assumes a major leap in clean coal technologies and ‘supportive’ government policies.

At the centre of the issues facing coal mining in South Africa is the national electricity supply parastatal, Eskom. The state-owned corporation has 16 coal power plants, two of them giants (Medupi and Kusile) still under construction. The official estimate is that coal still accounts for 87.5% of South Africa’s on-grid energy supply in 2018.

The most efficient way to get coal to the generator is to build the power station at the pit head. For many years Eskom managed this through the cost-plus or ‘tied’ model. The utility would pay the capital and operating costs of the mine, plus a small margin to incentivise the private-sector operator. However, since 2012, Eskom’s announced practice was to buy coal just from 50% plus black-owned mining companies, a more stringent empowerment requirement than government’s official 26%. This saw the international giants involved in the industry – Anglo American, South32, Exxaro and Glencore – sell off or otherwise restructure their South African assets, involving local interests. In early 2018, Anglo American sold its last major coal asset, New Largo, located near the under-construction 4 800 MW Kusile power station north of Witbank on the Mpumalanga coal belt. The buyer, Seriti Resources, is a 79% black-owned company that had previously purchased other Anglo coal assets. It is now Eskom’s largest ‘tied’ supplier.

Seriti’s chief executive, Mike Teke, believes there is a lot of life left in South African coal. ‘I know for a fact that global markets are not excited about coal simply because of the environmental issue, and the risks related to coal. But I will list this business if I can get a bolt-on, beautiful asset that has an export option with it,’ he says. That ‘bolt-on asset’ may well be the nearby Optimum Colliary mine, infamous as the asset acquired by the Gupta family in South Africa’s state capture saga. That tale is still under investigation by a judicial commission of inquiry.

Although Optimum has yet to be put on the market, Teke is excited by the prospect. ‘That mine can still go until 2033,’ he says, adding that it offers ‘huge value’. There’s ‘a 6.5 Mt [export] entitlement through Richards Bay Coal Terminal, and then you’ve got Hendrina power station next door, with a [coal supply] contract coming to an end… There’s an opportunity to reconfigure the contract and come up with a new way of doing things’, he says. In October, Eskom’s new board announced that the 50%-plus black ownership consideration had never actually been official policy but merely an ‘aspiration’. The board has looked through Eskom’s records and found no evidence that it had ever been officially adopted.

Another victim of managerial instability at Eskom was the cost-plus policy. In 2016 the utility announced that it would no longer pay capital and operating costs at ‘tied’ mines. It went further and suggested that existing tied mines in fact ‘belonged to’ Eskom and should be brought onto the utility’s balance sheet. The policy was reversed by the board in 2018.

Issues with Eskom were one of the main reasons for a steady drop in capital investment in the coal mining sector for more than a decade. According to MCSA, investment in coal has dropped an average of 10% per year since 2009, from ZAR7.3 billion in 2009 to ZAR3.8 billion in 2017. This impacts not only on revenues earned by the industry but also its ability to make the transition to ‘clean coal’.

Feris and Moodley argue that ‘both producers (miners) and users of coal (utilities) need to invest in the advancement of clean coal technologies (such as carbon capture and storage, underground coal gasification, and so on). These investments (which to an extent are already happening) will ensure that in the long run coal could continue to sustainably contribute to the economic development of coal-rich regions such as South Africa, Botswana and Mozambique’.

The master framework within which domestic South African factors affecting the future of coal mining will be decided is the Integrated Resources Plan (IRP). Until the latest version was released by the Department of Energy in August 2018, the industry was forced to refer to the last ‘official’ iteration – the 2010 version. The most recent version, which looks ahead to 2030, however, changes things rather dramatically. It drops all mention of planned nuclear plants and scales back new coal to two plants. With four elderly coal power stations (Hendrina, Camden, Kriel and Grootvlei) destined to be retired in the next 10 years, there will be a net cut-back in coal use. In fact the IRP sees coal dropping from its present 87.5% of national generation capacity to 46% by 2030. It will be replaced mostly by wind (15%), solar (10%) and gas (16%).

Hartmut Winkler, professor of physics at the University of Johannesburg, argues that a more rapid reduction on coal dependency is not possible. ‘A number of factors stand in the way of [South Africa’s] ability to move entirely away from coal,’ he says. In his view, ‘the biggest is that wind and solar power are intermittent, and new technologies haven’t yet been developed that allow for cheap and effective storage’.

With domestic usage planned to fall substantially, attention has turned to the prospects for coal exports. The main export terminal at Richards Bay has steadily increased in capacity over the years, from an initial 12 Mt when it was opened in 1976, to 91 Mt in 2018. This is more than the dedicated coal railway line, run by Transnet from the Mpumalanga coal belt, can deliver at full capacity. Feris and Moodley point out that 2017’s coal exports were ‘a record-breaking year for the Richards Bay Coal Terminal’. Transnet has announced that it will be expanding rail capacity over the next decade, at a cost of ZAR350 billion to ZAR400 billion. The logistics parastatal said that it plans to increase annual capacity to 120 Mt. It has already started construction of the dedicated line to the new Waterberg coal fields in Limpopo.

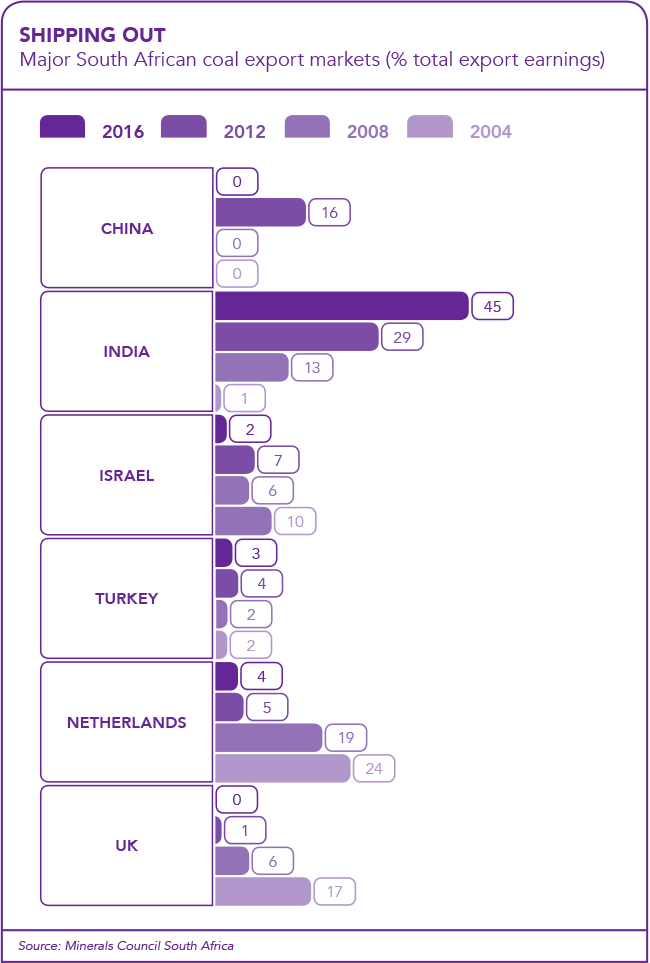

The market destinations of South Africa’s seaborne exports have shifted over the past 15 years. European countries dominated in 2004, with 24% of South African coal exports going to the Netherlands, 17% to the UK and 13% to Spain. But these figures have fallen precipitously as these countries have regulated to eliminate coal consumption. In 2016, exports to the Netherlands were down to 4% of the total volume, Spain was 1% and the UK was zero.

There has been a total shift from European markets to Asia. 45% of South African coal exports now go to India, up from 1% in 2004. Pakistan (7%) is the second-biggest destination. The Indian electricity market is dominated by coal, which accounts for 75% of electricity generation. South Africa’s Asian markets do not include China – which used to be significant (18% in 2011) and has implemented rigorous policies to reduce carbon emissions in recent years. No South African coal is currently exported to China. In the immediate future, exports markets are expected to keep South African coal mining going. But longer-term prospects might be rather gloomier.

The coal industry likes to talk about the potential of high-efficiency, low-emission (HELE) technologies as part of its future. Environmental considerations make HELE all but mandatory in virtually every market. But HELE works best with high-quality coal and South Africa’s competitors, such as Australia, are better endowed in this respect.