Mining legislation can attract or drive away investors while simultaneously promoting the safeguarding of people and planet. South Africa, despite its mineral wealth and sophisticated legal framework, is perceived as falling into the second category. It is, for example, worlds apart from Botswana – the continent’s shining example of enabling mining policy.

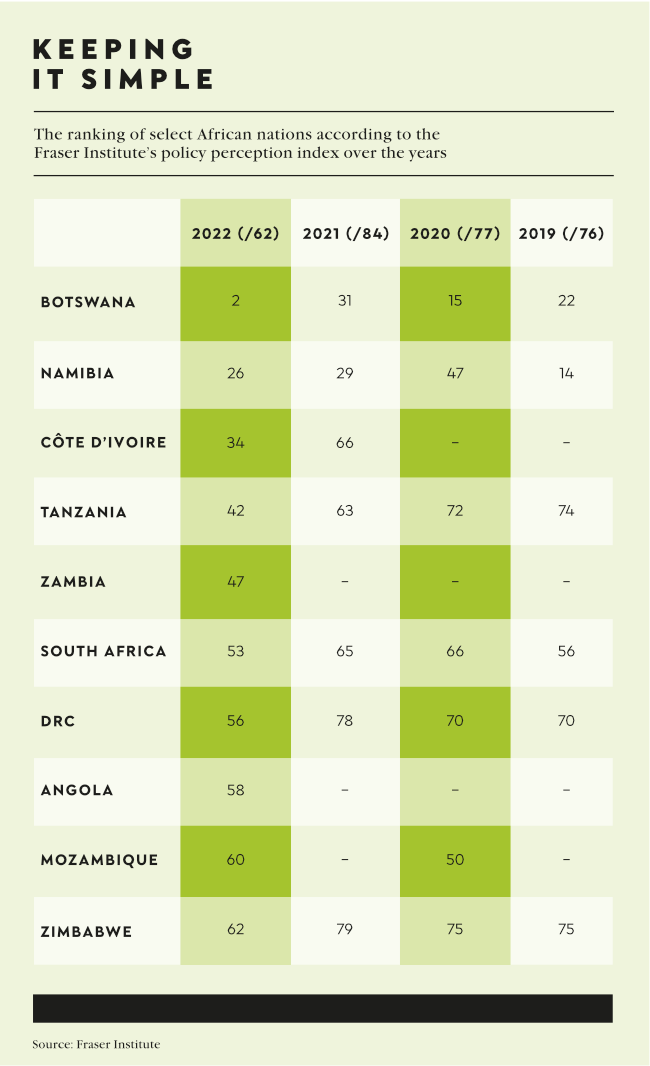

While Botswana firmly sits in the global top 10 of the Fraser Institute’s annual index of mining jurisdictions, which measures perceptions of onerous regulations, taxation levels and the quality of infrastructure, South Africa is hovering in the bottom 10. On policy perception, Botswana scored second-highest of all 62 surveyed mining jurisdictions in 2022, regarding policy questions such as uncertainty relating to the administration, interpretation and enforcement of existing regulations; environmental regulations; regulatory duplication and inconsistencies; taxation; uncertainty concerning disputed land claims and protected areas; infrastructure; socio-economic agreements; political stability; labour issues; geological database; and security.

Meanwhile in South Africa, there’s much room for regulatory improvement and better enforcement of existing regulations. Local mining industry stakeholders perceive some of their country’s legislation as ‘excessive and inconsistent’, saying it disincentivises investment in mining, according to the Minerals Policy Review Dialogues report.

The report focused on the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act (MPRDA) when it was commissioned by the Minerals Council South Africa and published in September 2023. ‘The participants in the Dialogues highlighted specific provisions of the MPRDA that warrant attention, including Section 11 regarding the need for ministerial consent for the transfer and encumbrance of prospecting and mining rights,’ writes Mining Weekly.

‘Section 43, as highlighted by the participants, makes it difficult to obtain a closure certificate for mines, while there is inconsistency around environmental rehabilitation obligations imposed by another piece of legislation, the National Environmental Management Act of 1998 [NEMA].’

So, what’s being done to bring regulatory certainty and consistency to South African mining? ‘It’s worth noting that in July 2023, the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy [DMRE] hosted a two-day MPRDA summit review to, inter alia, reflect on the implementation of the MPRDA and identify existing gaps in the MPRDA,’ says Carlyn Frittelli Davies, from ENSafrica’s natural resources and environment practice. ‘The summit is a step in the right direction and an indication that the regulator is aware of the regulatory challenges currently facing the mining industry. The most topical being the regulation of black economic empowerment in light of the 2021 judgment, which held that the mining charter is a policy document [rather than binding legislation].’

While the lawyer says the past year has not seen any groundbreaking legislation for the mining sector, she mentions a noteworthy Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) judgment on the interpretation of Section 11 of the MPRDA (which is one of the provisions flagged by the Dialogues report). Section 11(1) provides that ‘a prospecting right or mining right or an interest in any such right, or a controlling interest in a company or close corporation, may not be ceded, transferred, let, sublet, assigned, alienated or otherwise disposed of without the written consent of the minister, except in the case of change of controlling interest in listed companies’.

In the matter of Vantage Goldfields SA (Pty) Ltd and Another v Arqomanzi (Pty) Ltd and Others, the court had to consider whether Section 11(1) applies to an indirect change of the controlling interest – in a nutshell, whether ministerial consent is required.

Australia-based Vantage Goldfields had 34 shareholders, which in total owned 100% of the issued shares, explains the ENSafrica team. ‘In order to obtain funding for the implementation of its proposal to the rescue practitioners, Vantage Goldfields added Macquarie Metals – also a foreign-owned entity incorporated in Australia – as the 35th shareholder with the effect that Macquarie Metals acquired 98% of the total number of issued shares in Vantage Goldfields.

‘The SCA concluded that in light of the objects of the MPRDA, Section 11 must be interpreted as including both direct and indirect cessions, transfers, leases, etc and a change of control by the issue of new shares in a company that controls the mining right.’

This wider interpretation intends to restrict consent-avoiding attempts, such as complex intra-group restructuring or share-based financing in order to change the controlling interest of the mining right.

‘It is now clear that the Section 11 consent requirement will be considered on a “substance over form” approach,’ says law firm Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr. ‘The DMRE is entitled to cast its net wide in the exercise of its powers by taking into account the complex structures of company groups, even if this results in Section 11 having extra-territorial application to holding companies outside South Africa.’

On the environmental front, the mining industry is experiencing legislative changes intended to clean up some administrative and regulatory issues associated with the roll-out of the One Environmental System in 2014.

Most, but not all, of the sections of the long-awaited National Environmental Management Laws Amendment Act (NEMLAA) IV, came into force on 30 June 2023, says Paula-Ann Novotny, senior associate at Webber Wentzel.

‘The act aims to deter non-compliance with environmental laws by, among other things, introducing new offences, increasing the quantum of fines and administrative penalties where laws or licences have been contravened, and extends enforcement powers to enable more widespread enforcement of environmental laws.’

NEMLAA IV has, for example, extended the authority to issue directives to municipal managers, which will broaden the enforcement against those committing environmental transgressions. ‘This development is a game changer, which may result in an environmental enforcement blitz, particularly at the municipal level,’ says Webber Wentzel’s environmental team.

‘Provisions relating to financial provisioning – both mining-specific and general – under NEMLAA IV have also seen the light of day and are operational. This sets the scene for the replacement Financial Provisioning Regulations to be finalised to replace the 2015 laws,’ says Novotny. ‘Some of the changes under NEMLA IV that will seriously impact the mining industry are still expected to be introduced soon.

‘These include the regulation of residue stockpiles and deposits, which will be removed from the Waste Act and placed under the ambit of NEMA. The proposed changes to the definition of waste were found by the Constitutional Court to be unconstitutional and invalid, owing to the procedural defects in their enactment. Subject to transitional arrangements, a waste-management licence will no longer be required to authorise residue stockpiles and deposits, but rather an Environmental Authorisation and approved Environmental Management programme under NEMA.’

Another proposed change will subject Air Quality Act offences to stricter consequences and penalties. ‘The proposed Section 47A of the Air Quality Act – where no such provision previously existed – will enable a licensing authority to revoke or suspend an atmospheric emission licence,’ says Novotny.

‘This will be based on evidence that the licence holder has contravened the act or a licence condition, including that the contravention will be considered to have a detrimental effect on the environment, including health impacts.’

These recent and proposed changes in the legislative landscape show that South Africa’s lawmakers are trying to carefully balance the needs of the people and planet with an enabling policy for a profitable mining industry.

‘The new legislation is mainly intended to address some specific gaps and shortcomings in the regulatory framework,’ says ENSafrica’s Frittelli. ‘Legislation might appear to be comprehensive but upon its application, shortcomings become evident and that necessitates the addition of further legislation.’ How these legal changes will be implemented is a different story.