Mining can be a risky line of work – and not only in the way that most would imagine. People often see mining’s archetypal danger as a caved-in roof, preceded by the creaking of supports in a dark subterranean stope. Falls of ground and other workplace accidents do still pose a serious risk, even though improved safety practices have greatly reduced the number of deaths and injuries. In March, seven mineworkers died in a landslide at Glencore’s Katanga Copper operations in the DRC – even stringent safety practices can’t entirely eliminate physical risks of this kind.

Apart from these immediate dangers, however, the broader working and living environment for mineworkers (and the communities in which they make their home) raises a far broader set of challenges around disease and general health. It’s long been recognised that mining communities face an increased risk from certain diseases, and recently there have been sustained efforts to improve mineworkers’ health away from the immediate mine site, with developments across the continent driven by governments, transnational programmes and individual mining companies.

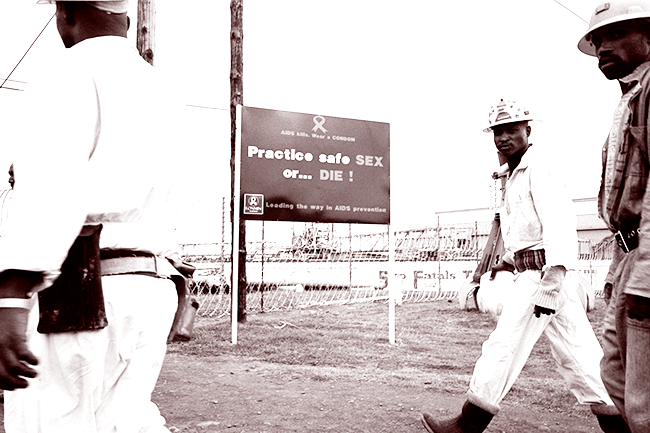

Several features of mining life mean that mineworkers are more exposed to certain diseases, although these vary across different African regions. Mining personnel are often drawn as migrant workers from a wide area or even several countries, increasing the spread of diseases as they converge on a single mine and its settlements – most notably HIV/Aids and other sexually transmitted diseases.

In addition, mines are generally located in remote areas and surrounded by dense bush, particularly in West and Central Africa, and this can increase exposure to insect-borne diseases such as malaria. The nature of mining work, with exposure to harsh mineral dusts, can also increase the risk of infection with pulmonary problems, including TB. In Southern Africa, TB became established on the mines, from where it spread to broader populations across the region.

Aids, malaria and TB are the three principal diseases of concern for miners in the same way as for general populations, but other diseases pose a risk too. In remote parts of Central Africa, mining communities often have better water supply than nearby settlements, but cholera can still break out with devastating effect. Mines are also vulnerable to any large-scale outbreak that threatens the movement of people or material supplies, and the recent Ebola epidemic brought several major operations to a standstill in West Africa.

Beyond the infectious diseases, many mining houses now accept responsibility for a much more comprehensive provision of healthcare in their stakeholder areas, sometimes even extending to infant and maternal health in surrounding settlements, or to more holistic ‘wellness’ programmes that emphasise general fitness and mental health. There are many examples to be found, both for broad-based public health and specific diseases.

The broader working and living environment for mineworkers raises a far broader set of challenges around disease and general health

In terms of general ‘wellness’, a new programme has recently been implemented at Vedanta Resources’ Konkola Copper Mines in Zambia. Here, in addition to standard health provision, the company has established a monitored programme that encourages workers to walk a minimum of 10 000 steps every day or play a range of sports.

In July, Vedanta CEO Tom Albanese (formerly the head of Rio Tinto) said that the miner has ‘a 50-year vision for this company. We need [workers] to be healthy to help the company realise the vision, hence the need to implement such wellness programmes that promote the health of the workers’.

That said, long-term ‘keep-fit’ programmes of this kind are still relatively rare, and most companies remain focused on healthcare essentials. Anglo American’s operations in South Africa provide a good example of an all-round programme. The company runs the world’s largest private sector HIV/Aids-prevention initiative, with more than 92 000 employees and contractors receiving HIV testing and counselling each year, and around 5 000 employees receiving treatment for HIV.

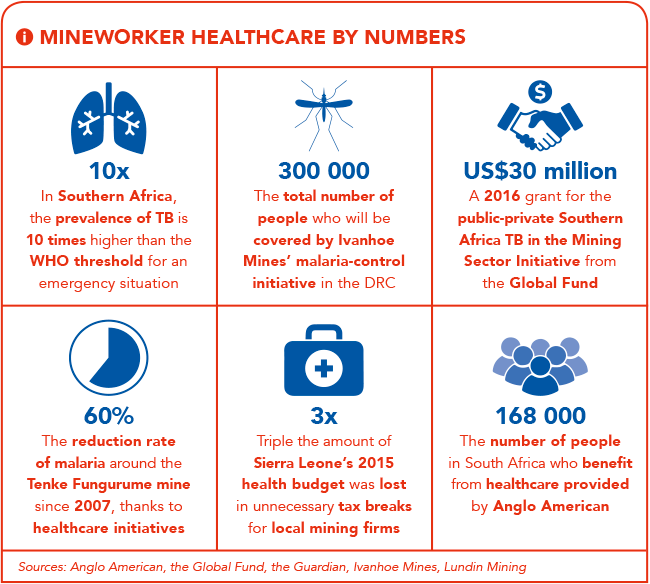

It operates a concurrent TB-testing programme, and funds the provision of general health services through local clinics. According to the company, around 168 000 people in South Africa benefit from its annual healthcare spending. Anglo also funds general public health measures through financial involvement in the Global Fund to Fight HIV/Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisations.

While most mines run employee health programmes, many also extend these services to their neighbouring communities. One such example comes from the Tenke Fungurume copper and cobalt mine in the DRC, co-owned by China Molybdenum and Lundin Mining. The mine runs an expansive programme of village sanitation and preventative health – the provision of drinking water to around 60 villages with additional urban water distribution networks has significantly reduced the incidence of cholera in the area surrounding the mine.

Aids, malaria and TB are the three principal diseases of concern for miners in the same way as for general populations, but other diseases pose a risk too

A concurrent malaria-prevention campaign (whereby houses have been sprayed and insecticide-treated bed nets distributed) has helped reduce the local prevalence of the disease by 60% since 2007. The mine also participates in various state-led HIV-control initiatives.

Many large mines run similar programmes. At Randgold Resources’ operations, for example, free essential medical services are provided to all employees, their families and other community members within a 10 km radius of the mines.

Other companies have gone further with regard to specific diseases. In 2014, Ivanhoe Mines announced the discovery of the world’s largest undeveloped copper deposit at the Kamoa project in the DRC, one of three operations it now runs there. At the end of 2015, the company launched a cutting-edge malaria-control initiative, in tandem with the DRC government and Canadian cloud-computing firm Fio Corporation. Ivanhoe will sponsor a three-year implementation of Fio Corporation’s intelligent diagnostic devices for a population of about 300 000 people, allowing data-driven analysis and response for malaria control.

‘Prompt capture of dependable data from screening tests is an essential step to help ensure that accurate and consistent diagnoses are made, which will help to build a secure foundation for the future delivery of large-scale, effective prevention and treatment activities,’ says Ivanhoe CEO Robert Friedland.

‘Ivanhoe is privileged to be in a position, with our partners, to provide new resources to support established healthcare objectives and to help ensure that the latest tools are placed in the hands of trained front-line workers, here in the DRC, where they will make a difference.’

While some mines have a clear impact in terms of improved health in their project areas, the greatest public health gains are likely to come from national or international co-ordination of mining firms with the state, transnationals and NPOs – linking the spending power and local access of mines with population-scale public health expertise. There have been several ambitious initiatives in this area.

The Mining Health Initiative, which is funded by the World Bank and the UK’s Department for International Development, looked at ways to integrate local mine health with national healthcare aims, and has published a set of best-practice standards for this kind of public-private collaboration.

The greatest public health gains are likely to come from co-ordination of mining firms with the state, transnationals and NPOs

In February this year, a new and expansive public-private initiative was announced. Funded with a US$30 million grant from the Global Fund, the Southern Africa TB in the Mining Sector Initiative is designed to bring together all role players – including governments and mining companies, labour unions, civil society groups and health researchers.

The grant extends to 10 countries, namely Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. The aim is to develop a comprehensive region-wide model for controlling disease – offering a far greater chance of success than current national efforts, which cannot account for dispersal of the disease through labour migration.

‘For over a century, we have dealt with a seemingly insurmountable challenge,’ says Donald Tobaiwa, head of the initiative’s regional co-ordinating mechanism. ‘With this grant, we seek to force a paradigm shift in the way we have addressed TB in the mining sector, and set new standards worthy of emulation.’

The extent to which mining companies have become the central providers of healthcare in some parts of Africa is a mixed blessing. Some observers, such as development consultancy Health Poverty Action, argue that it would be preferable for African states to raise royalty rates and use the revenues to strengthen national health systems.

There’s a clear case for bolstering government healthcare in many countries and getting a fair deal from natural resources. However, the history of state-led healthcare doesn’t necessarily show that additional revenues will be directed towards remote rural provision.

The distribution of Africa’s minerals has resulted in some mines being located in areas beyond the reach or inclination of other health providers. Under these circumstances, responsible firms can make a major difference.