In 2015, minerals and metal prices plummeted and although they have subsequently seen an uptick, the trauma has left deep scars on the mining industry. The world’s biggest companies found themselves financially stretched and committed to huge projects that were simply not viable.

Although the global corporates have subsequently unwound these unsustainable positions, in the process dumping assets at fire-sale prices, the outcome has been an entrenched degree of caution not seen since the 20th century. Financiers are much less inclined to expect good returns from mining.

The Preqin private capital tracker – which records investment capital raised worldwide by unlisted funds – found interest in mining investment in Q2 2017 to be at its lowest level in six years. At the end of 2016, the funds tracked were sitting on a war chest of US$181 billion but just US$5.5 billion (3%) was destined for the mining sector.

Elsewhere, it has been observed that none of the mining majors are undertaking big solo greenfields investments. All are looking for partners to share the risk. Mark Bristow, CEO of London-listed African gold miner Randgold Resources, has stated that ‘the mining industry has lost its nerve’. Ivan Glasenberg, CEO of Swiss-based Glencore, the world’s third-largest miner, has publicly stated that his company will not be undertaking new green fields projects ‘for a while’. Instead it will concentrate on the less risky and less expensive approach of incrementally expanding existing mines as well as acquiring existing assets from other companies.

The new-found conservatism that pervades mining majors has profound implications for mining in Africa. In the continent’s oldest and only ‘mature’ jurisdiction, South Africa, the implications are potentially serious. Already besieged by headwinds related to political animosity and sharp price increases in critical production factors such as electricity and labour, miners have been forced to act ruthlessly. Closures and cut backs in marginal operations are the order of the day.

Three major South African operators – AngloGold Ashanti, Sibanye Gold and Anglo American – have recently announced plans to lay off more than 20 000 workers in the immediate future. AngloGold Ashanti, the world’s third-largest gold miner, intends closing two ageing ultra-deep West Rand operations, namely Kopanang mine as well as Savuka, which forms part of the Tau Tona mine. The closures will affect 8 500 miners.

Most of South Africa’s gold mines are ageing. AngloGold Ashanti stressed that the closures are entirely a result of the depletion of the ore bodies and have nothing to do with other local operating conditions. The company may of course sell what remains of the Kopanang mine to a specialised, probably local, low-cost producer who could keep it running for a few years. But it has made noises that suggest it is reluctant to exercise this option. It is aware of examples of other such sales – most notably that of Grootvlei to Aurora Empowerment Systems – which have simply led to exercises in asset-stripping by the new owners. If this were to happen in the case of Kopanang, it could embroil AngloGold Ashanti in intractable legal, environmental and labour issues.

However, the running down of South Africa’s gold mines is not unexpected. Sibanye Gold, which is itself the most successful example of the sort of low-cost local miner to which Anglo-Gold Ashanti would want to sell its depleted assets to, represents a step further in the cycle of decline. Its four mines were already old and marginal when the company acquired them in 2011. Now it is planning to ‘restructure’ two of them – Beatrix West and Cooke – cutting 7 400 direct jobs and about 2 500 indirect (contractor) positions in the process.

Not unexpectedly, South African mining unions have responded to these jobs cuts with anger. At the end of July, the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) called for a nationwide summit to ‘discuss’ the situation. Speaking to the issue raised by the closure of AngloGold Ashanti’s operations, it stated that it is ‘concerned that many mines are being mothballed, instead of sold to new owners who could save jobs’. There is little doubt that this issue will be at the forefront in business-labour relations in the near future.

However, organised labour is weaker than ever in South Africa. In the mining industry it is divided between the NUM and a much newer and more active union, the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (Amcu). The NUM, once a bulwark of the ruling tripartite government, now has a much more ambiguous relationship with the ruling party and reflects the factionalism of that organisa-tion. Amcu is deliberately outside the ruling alliance and has been highly critical of individuals such as Mining Minister Mosebenzi Zwane as well as Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa, who has extensive mining interests.

From the perspective of mining companies there are real problems in knowing who in organised labour to deal with and, more pressingly, what power they have to implement decisions reached between management and labour leaders. Business/labour bargaining processes have been conducted at a national level in South Africa since 1995, but there are now voices in the industry suggesting that mine-level agreements should replace centralised processes. The separate deal struck by Gold Fields at its entirely mechanised South Deep operation in April has been heralded as a sign that South Africa’s centralised collective bargaining structure is in the process of collapse.

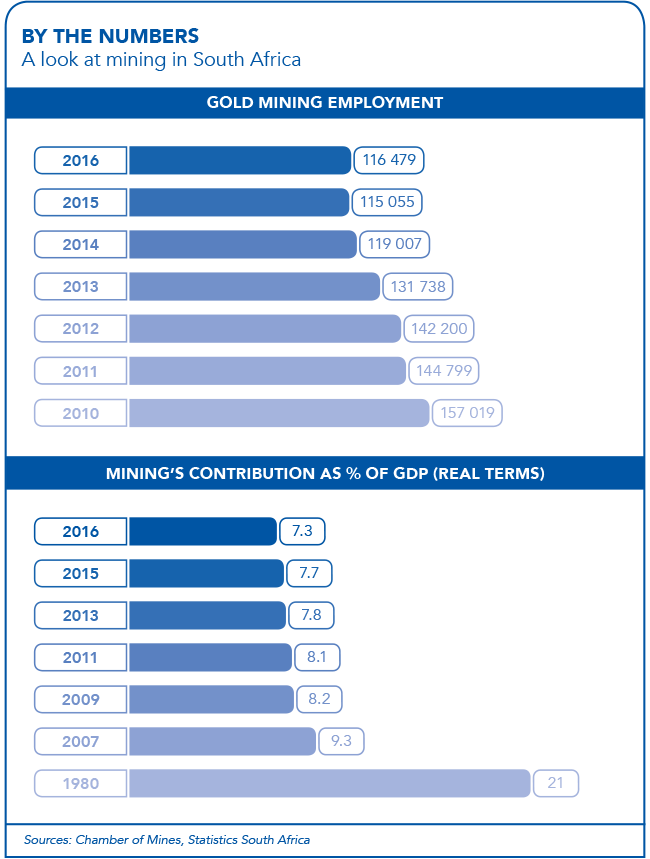

The South African mining industry has shed 70 000 jobs since 2012, according to the Chamber of Mines. Moreover the travails of the industry are demonstrated by figures suggesting that the sector as a whole ran at a net loss of ZAR50 billion from 2014 to 2016.

The present evidence of decline is simply a matter of long-known issues coming home to roost.

Issues in South Africa’s platinum mining sector are of most concern. The country possesses 80% of the world’s platinum reserves, and the metal – together with its close relative, palladium – accounts for 10% of South African export earnings. However, technology shifts suggest that the longer-term future of the metal is unlikely to be anything other than gloomy. Platinum’s primary use is as a catalyst in auto-exhausts, used to cut pollution. The much-heralded global clean energy transition is likely to cut demand severely. Battery-powered cars, such as those pioneered by Tesla, use about one-fifth of the amount of platinum. At the same time, these vehicles are made up of substan-tially greater amounts of copper and zinc.

Miners think long term. It can take seven or eight years for a large greenfield project to move from conceptualisation to production. Electric-car dominance may not even be that far off. Volvo announced this year that all its cars would be battery-powered or hybrids by 2019. Every major car maker has plans to build a battery-powered mass-market model to be sold at a price similar to that currently paid for a family saloon.

Glencore’s Glasenberg is certainly thinking about the implications for the mining industry. His company has shifted substantially into copper and zinc, even though it has no big new projects in its global pipeline at present and is looking hungrily at another clean energy input – cobalt. ‘The electric vehicle revolution is happening and its impact is likely to be felt faster than expected,’ says Glasenberg.

Miners in politically complicated jurisdic-tions such as South Africa and Tanzania may give the impression of simply going though the motions, working out assets while they can and looking to move on where possible.

Mining in Tanzania is subject to many resource-nationalism issues similar to those in South Africa. President John Magufuli is in the process of changing the enabling environment, hiking taxes and harassing companies to ‘beneficiate’ minerals before exporting them. Meanwhile, employees of Acacia Mining (the local subsidiary of Canada-based Barrick Gold) have been detained on poorly specified charges.

South Africa and Tanzania are countries that have taken on risky and probably self-defeating resource-nationalism strategies at a time when the industry, in general, is more risk-averse than it has been for decades.

It takes time for a mining company to refocus away from a particular national jurisdiction but this is undoubtedly happening, especially as other African countries – Côte d’Ivoire, the DRC and Mali – are not only resource rich but making strenuous efforts to reform their investment climates.

It may be that the nationalists’ loss will be the reformers’ gain. But even they are going to have to struggle against the winds of investor caution and technological disruption.