It’s become almost universally recognised in the mining industry that mechanisation (and its more ‘intelligent’ siblings automation and digitalisation) must replace the labour-intensive mining methods if South Africa’s mining sector wants to return to competitiveness. So the question in South Africa is not whether we’re going to further mechanise but rather how, where and when can it be done?

Local efforts – driven by initiatives such as the Mining Phakisa, the Mandela Mining Precinct and the SA Mining Extraction Research, Development and Innovation strategy – are accelerating local mining solutions through R&D and supporting home-grown original equipment manufacturers able to produce cutting-edge mechanised mining equipment suited for the unique local conditions.

‘Mechanisation is by no means a new concept to the South African mining industry, as varying degrees of mechanisation have been evident in our mines for over a century,’ according to Wits University’s Centre for Mechanised Mining Systems (CMMS), which provides key support to mines that are undergoing mechanisation. But new solutions are needed, particularly in the country’s deep underground stopes where workers are still physically involved in drilling, blasting and cleaning. Mechanisation will help remove them from potentially dangerous working conditions. Sadly, this is already causing major job losses but it’s believed that even without mechanisation, jobs will be shed as deep-level mining simply won’t be viable in South Africa.

The large opencast mines are already mechanised. The coal industry, for instance, has managed to create jobs moving from conventional mining to mechanisation (and partial automation) by increasing productivity, becoming globally competitive and growing the industry. Diamond mining is also widely mechanised. Petra Diamonds’ Finsch mine in the Northern Cape has been using the highly mechanised process of block caving for well over a decade and is considered the first to introduce a fully automated ore trucking loop underground.

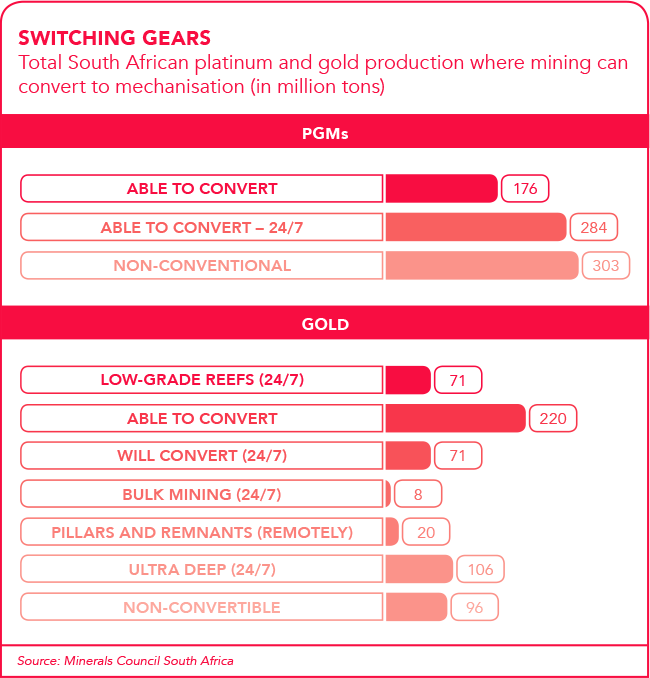

‘Today the biggest scope for further mechanisation in South Africa is in platinum and gold,’ says Declan Vogt, who was director of the CMMS before joining the Camborne School of Mines, University of Exeter. Vogt says Anglo American Platinum’s (Amplats) fully mechanised Mogalakwena surface mine on the northern limb of the Bushveld Complex was the major and lowest-cost producer of platinum by some margin.

‘Ivanplats’ Platreef is another massive new mine that is going to be fully mechanised underground,’ he says. ‘They’re also going to have low costs. Together with Mogalakwena, which is nearby, the two mines are going to take a big chunk of production from higher-cost underground operations.’ Platreef’s mineralised belt forms part of the Flatreef deposit at relatively shallow depths of 700 m to 1 200 m below the surface, and contains large quantities of platinum, palladium, nickel and copper as well as rhodium and gold. In October, Ivanplats MD Patricia Makhesha said in a statement: ‘Flatreef’s remarkably high-grade and thick, flat-lying ore body is ideal for safe, underground, bulk-scale, mechanised mining.’ The company’s mine plan calls for the addition of large, mechanised mining equipment, including 14 ton and 17 ton load-haul-dump machines, and 50 ton haul trucks to support the planned long-hole mining method. ‘Mechanisation works in greenfield sites and it is the future, but feasibility depends on the mine design,’ says Vogt. ‘It’s really difficult to introduce mechanisation into old mines, where the tunnels are not big enough to take machines. Yet if the mine is designed from the start with the option to take machines, it’s much more feasible.’

Another example is the US$2 billion project currently under way at Venetia diamond mine, which has built a high degree of flexibility into the design to extend the life of this profitable mine. De Beers CEO Phillip Barton said in an interview with Modern Mining: ‘The Venetia Underground Project has a ventilation system that caters for diesel-driven equipment and an electrical system that caters for electrically driven equipment, which gives us a great deal of optionality.’

Modernisation, as an overarching concept, includes mechanisation as well as automation and digitalisation – and sometimes the lines seem to blur. ‘In South Africa, mechanisation is usually taken to mean the use of machines to get work done,’ says Vogt. ‘Automation refers to the intelligent side of the business. For instance, the use of trucks in mining falls under mechanisation, while driverless trucks would be automation.’ Digitalisation is even more futuristic, incorporating big data, AI, internet of things sensors for data capture, and drones.

Minerals Council South Africa (MCSA) says more research is required for mechanised mining systems in platinum group metals (PGMs) to integrate tested equipment into a working system and provide real-time monitoring and control. For gold, a number of components (such as rock handling and support) need to be researched and developed with certain learnings taken from PGMs.

In its latest position paper on modernisation, the council explains that there’s need for the development of continuous mining machines that can cost-effectively cut the ore with reduced dilution. ‘The challenge in gold mining is that the rock is even harder than PGM-bearing rock and rock stress is very high, given depths of more than 4 km,’ it states. ‘24/7 mechanised mining systems would allow the exploitation of lower-grade reefs as well as deep high-grade reefs and high-grade pillar recovery.’ One case study refers to Amplats’ testing of equipment for hard rock, mechanised mines to operate with extra-low profile (XLP) and ultra-low profile (ULP) mining technology.

This type of equipment can operate in lower operating heights, greater depths and areas inaccessible to human mine workers. More specifically, it enables trackless mechanisation in narrow reef (1.2 m) stoping operations and low profile (1.8 m) room and pillar methods, according to DOK-ING, one of Amplats’ innovation partners. The Croatian firm (with the motto ‘don’t send a man to do a machine’s job’) has its roots in landmine clearing and it developed its first dozer for the South African mining sector in 2003: a small machine to assist with the cleaning of stopes after blasting, which has since been refined.

DOK-ING’s remote-controlled, diesel-powered MVD-XLP dozer can work in harsh mining and construction environments, such as inclines up to 30 degrees and high temperatures up to 50˚C. The dozer has a blade for digging and pushing the blasted ore in front of the machine and can handle 50 tons to 120 tons of ore per hour, with minimal maintenance. Referring to its most recent model, the company notes that ‘although designed for a certain kind of underground mining, its size and strength give it a number of other applications as well – in open and closed pits, narrow reefs, under conveyor belts, or even in construction work’. DOK-ING also recognises Sandvik and Atlas Copco as major players in the design and manufacturing of mining vehicles and equipment.

Locally, the CMTi Group is also developing ULP equipment specifically for the South African market. The company has made headway with its cutting-edge, remote-controlled mechanised equipment for narrow-vein mining operations, after years of partnering with large miners such as Sibanye Stillwater, Impala Platinum, Gold Fields, Harmony Gold and AngloGold Ashanti. CMTi is involved in Sibanye-Stillwater’s stope mechanisation programme, where its locally developed ULP machines – a remote-controlled multi-drill, and a sweeper and dozer prototype – have exceeded expectations in trials. In addition to the ULP technology, the company also offers a hybrid electric-diesel locomotive and integrated brake testing equipment. ‘Our solutions are the outcome of a process that was driven by the needs of the sectors, as opposed to a “push” approach from international manufacturers in the supply chain,’ according to CMTi MD Danie Burger. ‘By allowing the mines to drive the process, we have developed successful solutions for unique local operating conditions.’

The Isidingo Drill Challenge also focuses on local mining innovation. Initiated by the Mandela Mining Precinct and consulting firm RIIS, it’s an open call for the development of an improved rock drill that is lighter and more versatile than conventional ones. Three short-listed companies (Novatek, HPE and Fermel) were expected to compete to produce the final prototype in early 2019. ‘With the potential of becoming a widely-used new technology in deep-level mining and elsewhere, the challenge incentivises entrants to rethink the decades-old mining drill technology,’ says Sietse van der Woude, Minerals Council senior executive for modernisation and safety. ‘If we get this right, it will be good for suppliers, mining companies, employees and the country. Aside from sparking innovation, the challenge encourages new players to emerge.’

It’s another incremental step towards mechanisation, which will eventually require a wholesale change of thinking, says Vogt. ‘When you have worked in a certain way for a long time, it’s difficult to adjust to a systems change. Nothing you know, none of your experiences prepare you for what’s going to happen.

‘This applies to every level, from operators not knowing how to care for their machines to mechanics who don’t know how to maintain them, as well as to the managers who prioritise incorrectly because they’re just not used to how machines need to be managed.’

Some analysts are saying this human factor as well as labour strikes, combined with other challenges, may have played a role in Gold Fields’ so far unsuccessful conversion of South Deep from a labour-intensive conventional gold mine to a large‚ deep-level‚ mechanised operation. Bringing mechanisation into mining is challenging, says Vogt. But in a world where everything is becoming more high-tech, South Africa can’t go on sending men and women kilometres under the earth to manually extract minerals in increasingly risky and uncompetitive conditions. We may already have reached the point that a recent Reuters headline so bluntly described as ‘mechanise or die’.