In 2019 it became apparent that South Africa’s big mining companies are doing better than the jurisdiction as a whole. Share prices have soared and companies such as Impala Platinum (Implats), which seemed to be in trouble two years ago, are now looking to expand. The catch is that the expansion will be offshore.

As PwC’s September 2019 edition of SA Mine asserts, ‘the South African mining industry requires a revitalisation to regain its lustre’. Firmer commodity prices and a weaker rand have seen South Africa’s miners grow revenues this year. ‘However, if you take the rand out of [the equation], then growth has remained flat,’ says Andries Rossouw, PwC Africa energy and resources leader. Miners’ earnings are dollar denominated while their local costs are incurred in rands. But weak currency levels provide only a short-term cash injection. ‘This is not a long-term solution for the industry,’ he says.

At the Joburg Indaba in October, mining executives complained about the regulatory uncertainties still hanging over the industry. The Mining Charter, gazetted by the government last year, is still a bone of contention between industry representative Minerals Council South Africa (MCSA) and Gwede Mantashe, Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy. Mantashe wants to increase the proportion of mandatory black ownership to 30%, up from the previous 26%. More contentious is his determination to see ownership levels ‘topped up’ when black owners sell out their shareholdings. The MCSA and the minister each confirmed at the indaba that they were prepared to go to court over the matter.

Anglo American CEO Mark Cutifani argued at the indaba that the disagreement harms investor confidence. ‘Investors must believe that we have confidence in our industry, economy and institutions if they are going to invest. We cannot achieve this when we keep pulling from different ends. We need an aligned voice, bringing labour, government, non-governmental organisations and mining companies to promote the South African mining industry,’ he said.

There are other uncertainties too. The price of electricity is not stable, given the indebtedness (ZAR450 billion) and loss-making business practices of state-owned electricity supplier, Eskom. While the utility is no longer a reliable supplier, miners complain that their own efforts to install on-site back-up generators (mostly solar PV) are drowned in red tape. Labour relations remain fractious, especially given retrenchments at deep-level gold and platinum mines. Rossouw argues that the uncertainty is preventing substantial greenfields investment in the industry. ‘While capital expenditure has increased, no significant capital expenditure has been made in large-scale new projects,’ he says.

The effects of the carbon tax introduced in June 2019 are also unclear. Rossouw does not believe that the first (transitional) phase of the carbon tax regime will be particularly costly to miners. But the second phase, due to be implemented from 2023, may be a different matter. Eskom expects a carbon tax liability of ZAR11.5 billion in phase two, while Harmony Gold has said it will be liable for ZAR3.9 billion. Rossouw believes carbon taxes are necessary in terms of South Africa’s obligations under the Paris Agreement, yet he is worried about their impact on the competitiveness of the jurisdiction.

The big picture suggests that South African mining is in a transition from conventional deep-level operations to shallower, mechanised mining. Most of the big local miners have grasped this nettle in recent years, closing expensive gold and platinum shafts and concentrating on shallow, often open-pit resources, which lend themselves to machine mining. The Sibanye-Stillwater platinum operations have seen shafts closed at both its main recent acquisitions in the sector – the former Anglo American and Lonmin mines.

Sibanye-Stillwater CEO Neal Froneman said in September that the company had achieved savings of ZAR1 billion on its older Rustenburg assets. ‘We have proven these mines to be of decent quality with a lot of potential and we’ll achieve similar results with our most recently acquired Lonmin assets,’ he said. Another platinum miner, Implats, has closed five out of 11 shafts, and is considering cutting 13 000 jobs.

In short, the mines in South Africa have led the way towards a leaner and more efficient mining industry that is now reaping the rewards. Anglo American has probably gone further and faster than any other company. Its two major remaining South African assets are both huge open-pit operations – Kumba Iron Ore and Mogalakwena platinum mine. Anglo divested from its South African assets on a large scale as part of a global restricting in the wake of the commodity price collapse of 2015. It no longer owns any underground platinum mines, thermal coal or gold assets.

The results, for company bottom lines and valuations, have been spectacular. Free cash flows have doubled in 2019 while earnings and dividends are at a five-year high. The JSE Mining Index has outperformed the All-Share over the last two years. The market cap of the top 10 mining companies on the JSE has almost doubled over the last year, from ZAR482 billion in mid-2018 to ZAR884 billion in August 2019. Anglo American was valued at ZAR251 billion in August 2019, up from ZAR81 billion in June 2017. Implats grew in value from ZAR27 billion to ZAR69 billion over the same period, while Sibanye-Stillwater had climbed from ZAR21 billion to ZAR56 billion.

Implats is using its recently generated cash flows to diversify outside the South African jurisdiction. It is in the process of acquiring North American Palladium, following in the footsteps of Sibanye, which acquired the other major US palladium producer, Stillwater, three years ago. Implats CEO Nico Muller played down the attractiveness of geographical diversification but admitted it would be ‘attractive’ to ‘operate in a jurisdiction without power cuts’. Some commentators have been blunter. ‘[This] provides a hedge against some of the socio-economic, political and structural risks the company faces in South Africa,’ according to Christopher Nicolson, analyst at RMB Morgan Stanley.

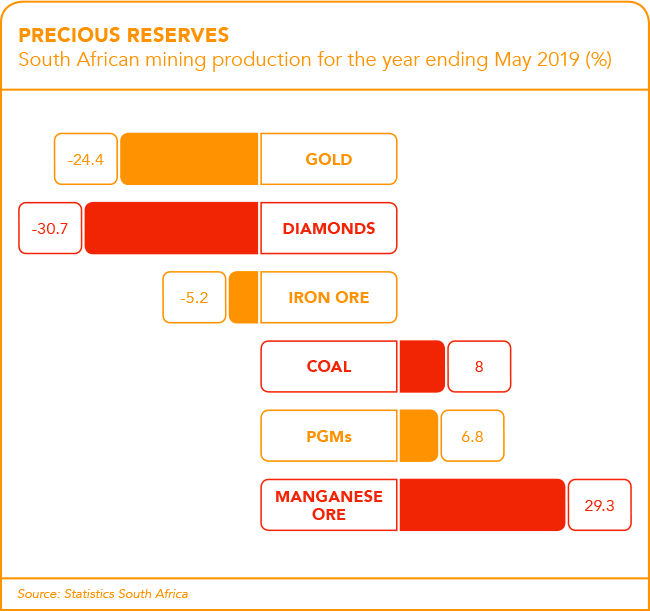

But not all mining sub-sectors have done equally well. Platinum’s transition has been the most spectacular. Gold, however, continues to decline, weighed down by ageing resources and the need to go to ever-more expensive depths. Indeed, in 2019, South Africa’s gold production dropped below that of Ghana’s, making the country only the second-biggest producer in Africa. However, the big miners have insulated themselves from this declining sub-sector. AngloGold Ashanti no longer holds any South African assets.

Many shafts have either been shuttered, including Tau Tona, or sold to smaller low-cost operators such as the previously little known Chinese company Heaven-Sent SA Sunshine Investment Company (Kopanang). Even Sibanye-Stillwater, which started life in 2013 when Goldfields separated out four aged gold mines, is no longer entirely dependent on the sub-sector. The company’s August financial results suggest that gold now accounts for less than half its earnings. Indeed the gold division was operating at a loss in the first half of 2019 after a bruising five-month strike.

Coal remains the biggest single sub-sector in South Africa, accounting for 24% of production. However, it is also a sub-sector beset by uncertainty. Part of this is related to the widespread global animus against fossil fuels. This is the reason given by mining majors Anglo American and South32 for selling their South African thermal coal assets. Both have gone or are going to black-owned South African companies, Siriti Resources and Exxaro. The new buyers face a number of issues. First, there is no appetite among local banks for financing coal developments.

Three of the country’s four major banks (Standard, FirstRand and Nedbank) have given in to shareholder activism and announced a moratorium on coal investments. Second, two-thirds of South Africa’s coal production is purchased by Eskom, which has for decades provided a steady, if unspectacular market. But in October it was revealed that three Cabinet ministers (Mantashe, Pravin Gordhan of Public Enterprises and Ebrahim Patel of Trade and Industry) had asked the industry to consider ‘cost reductions’ (in other words, cheaper coal) in order to help bail Eskom out of its debt predicament.

South32’s announcement, that it would be prepared to sell its thermal coal operations (to Siriti Resources) for next to nothing, looks far from irrational. There are other signs of a transition to a less precious metal, more industrial commodity-based mining industry. Although coal and iron ore production have plateaued in 2019, there has been new investment in zinc while production of another industrial commodity, manganese, has continued to soar. Production increased 34.3% in the year to August 2019, having increased 16.9% in the previous year.

2019 has been a more optimistic year for the South African mining industry. Cutifani argued at the indaba that it is necessary that it continue to maximise its positive impact. ‘The sand is shifting beneath our feet: if we cannot make a demonstrable positive contribution to society, our businesses will not be sustainable.’ He went on to spell out a vision that his South African peers will probably share: ‘I hope that mining will be unrecognisable 40 years from now, that it will be a trusted partner in economic development and a global leader in technical sophistication, its approach to environmental sustainability, and in its relationships with host governments, communities and broader society.’