Aspiring junior miners face intimidating hurdles. Yet some companies are managing to raise funding and develop greenfield projects in Africa, sometimes in destinations that have deterred their bigger peers. What these firms have in common are supportive shareholders, experienced management and commodities that appear to present good medium-term prospects.

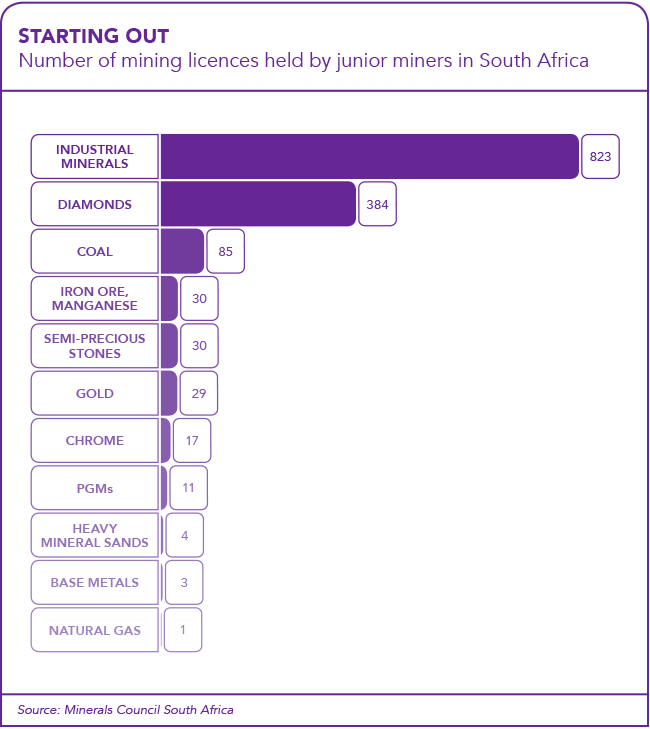

In a February 2019 report, the Minerals Council South Africa (MCSA) estimates that, in 2018, junior miners represented about 10% of the South African industry, with revenues of ZAR54.4 billion. Small mining companies (defined by Statistics South Africa as having ZAR2 million to ZAR105 million turnover) spent ZAR293 million on capex in 2018.

Although junior and emerging miners are important contributors to the economy, with considerable potential, South Africa’s regulatory landscape often puts them at a disadvantage. The various versions of the Mining Charter are aimed specifically at large-scale, deep-underground miners, who are significant employers and revenue generators. Even those miners battle to meet some of the charter’s requirements on empowerment, employment equity and training, housing, and social and labour plans. It is many times harder for small companies. ‘The one-size-fits-all legislation is ill-conceived,’ Bernard Swanepoel, well-known mining entrepreneur and organiser of the annual Junior Indaba, said at last year’s event.

For example, the requirement for mining companies to have 26% black empowerment shareholding (or 30% for new and renewed mining licences) is impractical for companies that need to raise money on a regular basis, since many BEE partners have little funding themselves and have to be vendor-financed. Vendor financing is generally structured around repayment from dividend flows, but exploration companies and junior miners do not usually generate dividends. This reality is recognised in the latest revised version of Mining Charter III, which provides some specific exemptions to mining rights holders in the categories of less than ZAR150 million turnover a year or those with turnover of between ZAR10 million and ZAR50 million per annum. That, unfortunately, is not enough to give the junior mining sector the relief it needs. At last year’s Junior Indaba, SRK Africa partner Mark Wanless said junior miners also needed a more effective Department of Mineral Resources (DMR) portal to show the licences and areas that are available for new entrants, and a faster licensing process.

According to the Anglo Khula Mining Fund, the problems facing junior miners include a shortage of appropriate advisers and lack of access to development capital. ‘Investing in early-stage exploration is risky and requires a patient investor,’ a spokesperson for the fund says. ‘This is the area that a majority of financiers in South Africa tend to shy away from. Most of the commercial institutions will start getting involved in project funding post pre-feasibility or post the completion of a bankable feasibility study. Access to capital to get to that point remains a big challenge.’

Paul Miller, co-founder of the CCP 12J Fund, which targets low-risk, secondary and ancillary mining projects on existing sites, says junior miners can only exist where three overlapping criteria are in place. The first is that the state should spend money on exploring South Africa’s geological endowment, and make that information available to everyone. The second is that investor sentiment has to be positive. The third is that there has to be proper policy and regulation in place.

Miller says South Africa is failing on all three aspects. There has been little or no recent exploration using modern techniques, and the resulting information is not widely available. Investor sentiment is toxic. South Africa’s Constitutional Court has confirmed that the DMR is incompetent and two regional offices were closed because of corruption. ‘Obstacles range from the risk-averse nature of South African banks through to the need to develop pre-feasibility studies and presentable bankable documents,’ according to Grant Mitchell, author of a 2016 study commissioned by the MCSA into challenges facing junior miners. Mitchell quotes a BEE entrepreneur who says: ‘There are no proper support mechanisms for new entrants to the industry. In the beginning we went to the various financial institutions as well as the Industrial Development Corporation [IDC] but we got nowhere. The IDC wanted pre-feasibility studies but we did not have the funding to do these. Eventually BHP Billiton helped us.’

Last year the DMR announced it intended to launch a fund with the IDC to help junior miners, but the details remain unclear. There have been other efforts in the last decade to launch private equity funds targeting junior mining ventures – with mixed success. In 2003 the New Africa Mining Fund (NAMF) was set up to finance junior miners. Its investments included some ventures that succeeded, such as Petmin’s Somkhele anthracite mine; and others that eventually failed, including South African Coal Mining Holdings.

A second fund was launched in 2011, called NAMF II, but it closed just two years later because it was hard to source opportunities due to ‘the continuous downward trend’ in the junior mining sector. The Pamodzi Resources Fund I – which was targeting US$1.3 billion of investments and backed by AMCI Capital and First Reserve Corporation – put new investments on hold in 2009, saying it was affected by the downturn in resource prices.

There have been two other recent fund launches targeting junior miners using the Section 12J incentives of the South African Income Tax Act. The funds are the JSS Empowerment Mining Fund (established by Jaltech and Stefanutti Stocks), and the CCP 12J Fund (founded by DRA Group, Minopex, Concentrate Capital Partners and Stockdale Street). A JSS spokesperson says the fund’s future is under review by the board and that they would not respond to questions about it. Miller says CCP 12J has committed funds of ZAR220 million and can raise more as it finds opportunities.

The Anglo Khula Mining Fund, which targets small-scale, black-owned companies, has been around since 2003. The fund is a partnership between Anglo Zimele and Khula Enterprise Finance. Initial capital was ZAR40 million, which was topped up to ZAR200 million in 2008. By 2012, the fund had made 11 investments in companies employing a total of more than 800 people.

Several junior miners that started with listings on other exchanges, such as Australia’s (ASX), have managed to raise the first capital towards building new mines, usually with the support of one or two anchor shareholders. ASX- and JSE-listed Orion Minerals, which is developing a copper-zinc mine on the site of the former Prieska copper mine in the Northern Cape, South Africa, secured a cornerstone shareholder in Tembo Capital, and a strategic partner in an Australian mining group, Independence Group. Tembo is a private equity group that targets junior and mid-tier opportunities in developing countries. ASX-listed Prospect Resources is developing the Arcadia lithium project in Zimbabwe, which it describes as its flagship. Investors’ appetite for battery metals such as lithium has helped support the shares, and most of Prospect’s shares are held by the retail market.

Prospect has a seven-year offtake agreement with Sinomine Group, a spin-off of China Nonferrous Metal Mining, to deliver 40 000 tons a year of spodumene (for batteries) concentrate and 112 000 tons/year of petalite (for glass and ceramics) concentrate. Minergy Coal, which is listed in Botswana and headed by South African Andre Boje, is developing the Masama coal deposit in Botswana. Its two biggest shareholders are Energy Mineral Resources and Mining and the Botswana Public Officers Pension Fund.

Minergy raised BWP70 million from institutional investors in a private placement in early 2017, followed shortly afterwards by a listing that raised BWP2 million. It garnered another BWP24 million from shareholders in 2018. Alphamin, which is developing the Bisie tin mine in north-eastern DRC, was backed by a UK private equity fund, Denham Capital Partners, before it listed in Johannesburg and Toronto. Denham is advised by well-known South African mining entrepreneur Rob Still’s Pangea Exploration.

In 2011, Denham funded Pangea to find suitable investment prospects, one of which was Bisie, and subsequently the IDC also put US$10 million into the development. Bisie will take advantage of a very high-grade resource, in a rising tin market.

With the upturn in some commodities prices, there are signs – certainly among Canada’s junior mining sector – that investors are becoming more willing to invest. According to PwC’s 2018 analysis of the top 100 junior mining companies on the TSX-Venture exchange for the 12 months to end-June 2018, these miners raised CAD2.7 billion in this period, 6.5% more than in the previous year. Exploration and development-stage companies consumed the majority of this amount, as production-stage miners came to rely more on debt financing, which increased by 65.9%.

These are positive signs that capital, the lifeblood of juniors, is flowing again.