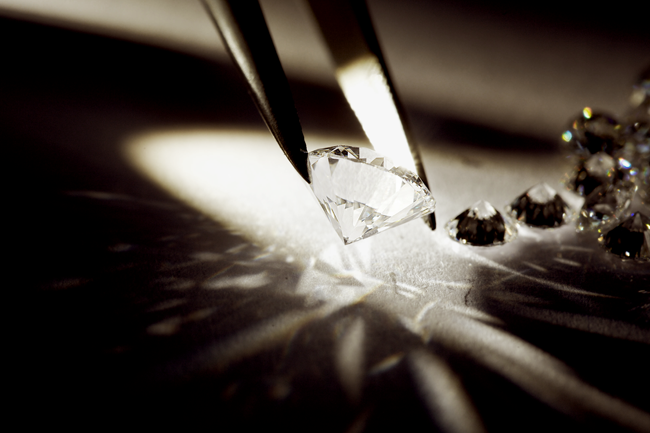

In October 2014, Canada-based firm Lucara sold a 203-carat diamond from its Karowe mine in Botswana for US$8.2 million. In April this year, it announced it had found a 341.9-carat gem too – as well as two other stones, each more than 100 carats. According to the company, the latest find was of ‘exceptional colour and clarity’.

Diamonds are not only a girl’s best friend, as Marilyn Monroe once sang – they’re pretty good for Botswana too. Since the precious stones were discovered in the country nearly 50 years ago, they have helped transform the tiny landlocked nation’s economy to the stage where its some 2 million inhabitants are reaping the benefits of among the highest living standards on the continent. According to a survey by US business magazine Global Finance, Botswana’s purchasing power parity per capita was US$14 792 in 2014, compared to South Africa’s US$10 466 and Namibia’s US$6 717.

In the words of former Minister of Mineral Resources and Water Affairs Archibald Mogwe, they were ‘a godsend’.

Diamonds are Botswana’s biggest foreign exchange earner. In 2013, polished diamonds worth BWP6.6 billion were exported, according to the Mail & Guardian. However, the industry also provides the largest pool of employment outside government services.

At the forefront of Botswana’s diamond industry is De Beers, which is 85% owned by mining giant Anglo American. It was De Beers’ geologists who uncovered the first diamond-bearing deposits at Orapa in 1967 following extensive exploration from the mid 1950s. The company operates the Debswana Diamond Company, in a 50/50 partnership with the Botswana government.

Debswana operates the Orapa, Letlhakane, Jwaneng and Damtshaa mines and according to an annual report, it ‘recovered 20.22 million carats in 2012, down 2.67 million carats on the previous year’. In doing so, it treated close to 22 million tons of ore.

In April 2015, Reuters reported the firm as saying it would ‘produce between 23 million and 26 million carats a year in the medium to short term’. Such has been the quality of the resource that globally Botswana is the biggest diamond producer in terms of value (Russia takes first place for output). According to KPMG, in fact, it accounts for around 24% of total worldwide diamond production.

Much of the credit for Botswana’s mining sector success can be attributed to far-sighted and progressive government policies. Right from the beginning the state recognised that a partnership with the private sector would be crucial to unlocking mineral wealth.

As KPMG put it in a report: ‘The country has a strong legal framework, low prevalence of civil unrest or disorder and minimal government interference in the mining sector.

‘Botswana also boasts infrastructure that is in better condition than several of its neighbours, which has assisted in boosting interest from international companies in the mining sector.’

The all-round positives have translated into it being one of the most attractive mining jurisdictions in the world. It ranked 26th worldwide in the Fraser Institute’s 2014 survey, one behind Namibia, the continent’s top-ranked country. However, on policy factors, Botswana is ranked number one in Africa (13th globally), up from 25th in 2013.

According to the Fraser Institute survey, Botswana showed improvement concerning almost all policy factors, including labour, skills, administration, interpretation/enforcement of regulations and security.

Transparency, simplicity and administrative efficiency have long been a hallmark of the Botswana Department of Mines, which falls under the Ministry of Minerals, Energy and Water Resources portfolio.

Mining licences are granted timeously and are valid for 25 years with the right of renewal. In terms of legislation, government has the option of acquiring up to a 15% working interest in a proposed mine (calculated by third parties), including the right to appoint up to two directors. If the option is exercised, the state contributes towards its shareholding. If it doesn’t, the option lapses.

Royalties are calculated based on the gross market value of production – precious stones are 10%; precious metals 5%; and other minerals 3%.

The country was also an early mover in Africa as far as beneficiation is concerned, with several diamond cutting and polishing factories set up. In 2014, around 3 750 skilled workers were employed, providing income for entire villages. Unfortunately, 2015 has seen this agenda run into problems.

In February this year, one of the country’s oldest diamond cutting and polishing firms, Teemane Manufacturing Company, closed. This followed news earlier that two other companies, Motiganz and Leo Schachter, were retrenching workers.

‘Botswana boasts infrastructure that is in better condition than several of its neighbours’

Roman Grynberg, senior researcher at the Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis, said Botswana faced beneficiation problems on several fronts, but that the big competition was from India where there are around 800 000 cutters. In a Sunday Standard article, he wrote that although wages between the two countries were roughly similar for diamond cutters, productivity and costs were not.

‘De Beers has said that the cost of cutting in 2013 ranged from US$60 to US$120 per carat in Botswana, while in India the range varied from US$10 to US$50 per carat,’ he wrote.

‘In other words, in the smaller diamonds, Botswana is six times more expensive than India. And for the larger, more expensive stones, it is almost three times as expensive because of low productivity and low cost of ancillary services, as well as the number of working days in the year – 232 in Botswana as opposed to over 280 in India. That is why Botswana is limited to commercially cutting one carat rough and above.’ Around 80% of diamonds excavated are under 0.2 carats.

The government is attempting to diversify the minerals sector. Botswana has deposits of lead, uranium, manganese, platinum and soda ash, among other minerals, as well as gold.

A number of small gold operators, such as Monarch, near Francistown, were utilising modern technology to salvage tailings but that mine has now been mothballed. In the west, sedimentary basins with potential gas and oil formations have been identified. However, coal is receiving the most interest from both government and prospectors.

Currently there is a single established coal mine, Morupule, near Palapye operated by Debswana. However, several other firms – including Chinese operators – are engaged in exploration. Large coal resources suitable for power-station use have been identified in eastern Botswana, and the government puts reserves at around 202 billion tons.

KPMG says: ‘Botswana’s coal industry is likely to see increasing investor interest in coming years, and has been identified as a vehicle through which to diversify the economy. The Chamber of Mines expects the country to export 115 million tons of thermal coal in the next seven to 10 years.

‘According to Business Monitor International, the country’s mining sector is expected to grow at an average rate of 3.7% during 2013 to 2017, to reach a value of US$6.13 billion. This is expected to be driven by the steady growth in diamond production, combined with an accelerated growth in coal output.’

Although no new coal mines have broken ground yet, the country is forging ahead with plans for large-scale production.

In January this year, Bloomberg reported that the Botswana Chamber of Mines wanted to use existing railway lines to ports in South Africa and Mozambique instead of waiting for a proposed line through Namibia.

‘You cannot sit down and wait for the Trans-Kalahari railway – that would be a disaster,’ the chamber’s CEO Charles Siwawa was quoted as saying. ‘The thing to do is to move on the available capacity.’

The 1 500 km heavy-haul line was earmarked to transport Botswana’s coal to Walvis Bay, and from there to China and India.