For a decade the global industry’s spotlight has shone on the more advanced gas production plans off countries on Africa’s east coast.

In general the transformational opportunities of regional gas have been at risk of slipping away from energy-constrained South Africa. But in late October 2013, oil and gas major Royal Dutch Shell said it was optimistic it would go ahead and spend an initial US$250 million drilling off-shore exploration wells in the Orange basin off South Africa’s west coast. Shell is confident ‘it will find something after drilling a few wells’, Business Day reported Shell South Africa’s general manager for upstream business Jan Willem Eggink as saying.

Earlier in the year Shell lobbied the South African authorities to extend proposed tax breaks for off-shore gas (that could benefit its Orange basin plans) to onshore fracking of Karoo shale gas.

‘Onshore UCG [unconventional oil and gas, which includes shale gas] requires long exploration and appraisal periods [up to 10 years] with many wells and pilot projects requiring a high upfront capital commitment that may not lead to any returns,’ Eggink told the parliamentary committee on finance.

‘Moreover, development and subsequent production in case UCG is proven, require high and extended investment and these projects in itself are not expected to generate net cash flows for possibly two decades,’ he said.

At the end of the year the South African government released an updated (and long awaited) revised version of its IRP (Integrated Resource Plan), which dates from 2010. The IRP models supply and demand of electricity over a 20-year period.

The latest IRP takes account of procuring the region’s natural gas as well as increasing the exploration of the country’s shale gas deposits.

Those deposits are said to be substantial, but it is a truism that in the oil and gas sector it is challenging to predict viable reserves – even using the most advanced scientific methods – without physical confirmation from expensive exploration drilling. Even after exploratory drills ‘prove’ reserves, ‘dusters’ (as dry wells are known in the industry), are still as common as ‘gushers’.

Up to now it’s been the potential off Africa’s east coast, particularly northern Mozambique, that has received the most attention from investors. But when it comes to proven reserves, Mozambique only ranked eighth in Africa as recently as 2012, according to the KPMG Oil and Gas in Africa report.

Nigeria comfortably leads the table. While there is already modest production from Mozambique, it is the advanced plans to ramp this up that have resulted in almost daily headlines in the world’s financial press.

Bloomberg describes the combined natural gas finds by Anadarko Petroleum of the US and Italy’s Eni SpA (ENI) in the Rovuma basin as the largest discoveries in a decade. Already Mozambican authorities have said they will announce the winning bidders to build four liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals and pipelines connecting them to the rigs by mid-2014.

The cost may be as high as US$20 billion and the plan is for gas production to start in 2018. However, a report in the Financial Times (FT) has questioned if it will be that soon. According to the FT, the surge in cheap US shale gas is luring Asian customers and threatening to postpone new gas production around the world. But with US shale gas production set to peak in around a decade, the long-term Mozambican gas story may still come to fruition.

Potentially the Mozambican processing terminals, which chill the gas to liquid, allowing it to be transported via sea, will result in the biggest export hub after Qatar’s Ras Laffan, according to Bloomberg. In the case of Mozambique the gain could be more direct than in many developing countries – domestic energy supply.

Because African producers generally do not have the infrastructure to convert oil and gas into energy and industrial chemicals, most of the raw material is exported. Consequently they miss out on some additional benefits of having energy sources on their doorsteps – security of supply and potentially lower prices.

The surge in cheap US shale gas is luring Asian customers and threatening to postpone new gas production around the world

But in Mozambique the development of gas power stations could see this relatively environmentally friendly and affordable energy source spurring manufacturing and commerce. Along with Mozambique, other countries in the region with advanced gas plans include Tanzania, Uganda and Kenya.

Curiously in energy challenged South Africa, where most electricity is generated from cheap but ‘dirty’ coal, there have only been limited indications of interest expressed in Mozambique’s gas finds by the South African government – although the IRP’s mention of regional gas could have changed that.

The IRP states the intention to reduce reliance on coal and add lower carbon (dioxide) emissions forms of energy. Yet no plans for major gas power stations have been announced. Admittedly construction is under way for two gas power plants in the east of the country, but these are only peaking power plants aimed at offering relief during times of high consumption.

While domestic energy security is hardly an issue unique to South Africa, it is unusual for an energy threatened country to shy away from pursuing gas power from a friendly neighbour. This is pertinent as potential local gas supplies are at best some way off.

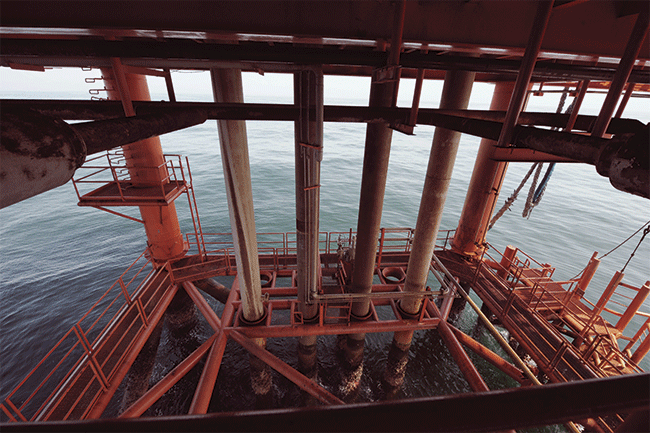

Shell’s plans for the Orange basin and hydraulic fracturing (or fracking) of the Karoo may be closer, but have yet to even enter the formal exploratory stage. Currently South Africa is not even in the top 20 of African countries with proven reserves.

It seems no one in government has perused a joint study on gas by the Norwegian government and the World Bank, which ‘points to energy constrained South Africa as an obvious market’. South Africa’s 2010 plan looked to build additional nuclear capacity ‘however, gas-fired power plants are emerging as a serious contender with the potential of Karoo shale gas’, says Dirk de Vos, a director at corporate finance firm QED Solutions.

‘But Mozambican natural gas could well render the extraction of Karoo shale gas uneconomic for generations to come. The attraction of gas is clear, in the generation of electricity, natural gas emits half the carbon dioxide compared to coal,’ De Vos says.

Ichumile Gqada, a researcher with the South African Institute of International Affairs’ governance of Africa’s resources programme, argues the state needs to consider investing in a gas terminal, enabling it to receive Rovuma basin gas.

‘If this is not done, this massive resource will bypass South Africa and be exported, to Asia and probably Europe,’ says Gqada.

What Gqada does not explicitly say is that South Africa, with its expertise and capital, may have a stronger mutual interest in developing regional gas power stations to benefit both countries – as opposed to Asian countries who may simply need the raw material.

There has been one South African gas experiment, however, that speaks volumes for the potential.

In 2000, before the global scramble for Mozambican gas, South African authorities, along with those in Mozambique, worked together with African energy giant Sasol to pipe Mozambican gas to South Africa.

The joint government and Sasol ownership of the pipeline is held up as one of the better functioning multinational government collaborations with the private sector (despite some complaints from Mozambicans that they did not benefit enough from the arrangement).

In energy challenged South Africa, there have only been limited indications of interest expressed in Mozambique’s gas finds

The first Mozambican gas arrived in 2004 and then in 2013 Sasol inaugurated South Africa’s largest gas power plant, with a capacity of 140 megawatts, at a cost of R1.9 billion, fired by Mozambican gas. A little reported fact is that Sasol is now 60% reliant on gas for electricity in South Africa, according to the company.

This power station not only eases the load on Eskom, but also feeds power back into the national grid. To date Sasol is the only direct importer of Mozambican gas and continues to invest in expanding the project.

However, it would also be wrong to say the concept of significant imports is completely dead in the water. The appeal is persuasive. With increased gas production relatively nearby, and a big market of South African customers, prices can drop sharply, as the US Energy Information Administration found in that country. Another attraction is the speed with which gas power stations can be built.

While government apparently is hesitant, intentions have been delivered more directly by some South African state companies. Eskom CEO Brian Dames has said the electricity utility is eager to pursue more cross-border electricity projects with its peer Electricidade de Moçambique (EDM).

‘We want to be involved in all aspects of (regional) projects, not just buying power, particularly in Mozambique,’ Dames said as long ago as 2012.

State-owned PetroSA has been long on plans but short on delivery to expand in both oil and gas since its own off-shore supply started running out. PetroSA is now interested in building a liquefied natural gas terminal off the nation’s south coast that may cost as much as US$510 million, according to Bloomberg. With the potential Mozambican supply, it may now have a stronger business case than in previous projects.

But, as usual, the action is from the East. Recently two Asian powerhouses announced deals to secure gas supply from Africa’s east coast. Singapore, over 7 000 km away from Tanzania, is the latest, with a transaction needed to feed its own South East Asian hub.

In November 2013 the Singapore state-owned Pavilion Energy, agreed to pay Ophir Energy US$1.3 billion for a 20% stake in three gas blocks off the shore of Tanzania, according to Bloomberg.

Earlier in 2013, India’s Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC) bought a 10% stake in Anadarko Petroleum’s gas field in the Rovuma basin for US$2.64 billion to secure its own long-term supplies, according to the FT. As Chinese and Thai companies have announced similar deals, it seems South Africa is still in slumber mode.