At the southernmost tip of the African continent, South Africa – bordered by Namibia, Botswana, Lesotho, Eswatini, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique – boasts a rich tapestry woven with threads of historical significance and cultural diversity. The narrative of this nation unfolds over centuries, shaped by the collision of indigenous cultures, European colonisation and the tumultuous waves of apartheid.

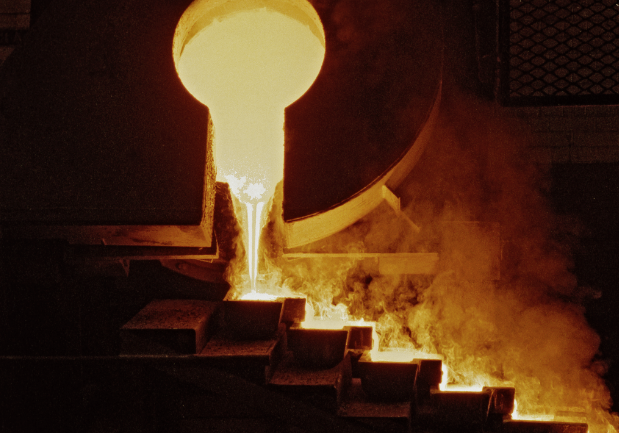

The late 19th century marked a seismic shift in South Africa’s economic landscape with the discovery of gold and diamonds. The Witwatersrand gold rush of 1886 and the prior unearthing of diamonds in Kimberley saw foreign investors flooding in, transforming South Africa into a global mining powerhouse. The newfound wealth fuelled infrastructure development, urbanisation and industrialisation.

The 20th century dawned with South Africa entrenched in institutionalised racism, formalised by the National Party’s apartheid policies. Nelson Mandela’s release in 1990 was a turning point, though, and negotiations led to the dismantling of apartheid and the establish-ment of multiracial elections. Four years later, in 1994, South Africa held its first democratic elections. Mandela became the nation’s first black president, and the African National Congress has been the ruling party since.

Challenges persist, however. Unemployment rates remain stubbornly high. Youth unemployment, in particular, paints a stark picture of unfulfilled potential. Despite efforts to stimulate job creation and skills development, the economic playing field remains uneven. Last year, after two consecutive quarters of growth, South Africa’s real GDP contracted by 0.2% in Q3:2023, with agriculture, manufacturing and construction the biggest drags on growth. ‘The agriculture industry declined by 9.6%, driven lower mainly by field crops, animal products and horticulture products,’ according to Statistics South Africa. ‘On the upside, finance, real estate and business services, personal services and transport, storage and communication were the largest positive contributors to GDP growth.’

Historically, the South African economy has been deeply intertwined with its mineral wealth, particularly gold and diamonds. Yet its heavy reliance on mining has also exposed it to the volatility of commodity prices, leaving South Africa vulnerable to global market fluctuations. The mining sector generates revenue through various channels, including taxes, foreign currency reserves derived from mineral sales and employment opportunities, among others. Challenges, however, abound – among them electricity constraints; logistical issues (which impact bulk commodity exports); fluctuating commodity prices and exchange rates; above-inflationary cost pressures; illegal mining; a shortage of critical skills; and a highly inadequate cadastral system.

The South African Mineral Resources Administration, the system currently in place, is notably flawed, and for years, mining companies have been calling for the establishment of a modern and transparent online cadastre to curb corruption in the licensing process and encourage essential investments in industry exploration. Yet, despite an announcement in August last year that a winning bidder to provide the long-awaited mining cadastral system would be announced before the end of October, little has yet come to light. Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy Gwede Mantashe has since hinted (at the time of writing) that an announcement could be made soon.

Time is of the essence though. In early December 2023, Mantashe told Parliament that 2 525 mining licence applications had been received since the beginning of the 2023/24 financial year, but that none had yet been finalised. Curiously, in a media statement released on 17 January 2024, the department changed its tune, stating that ‘the DMRE has finalised 2 041 applications in the current financial year. The department is committed to being efficient and transparent in processing mining applications’.

On the upside, however, considering the context of a just energy transition and net zero, the ‘big six’ critical minerals – copper; PGMs; lithium; nickel; cobalt; and rare earth elements – hold much potential for the country. ‘There’s a clear shortage of energy metals [globally] with committed mine production nowhere near projected demand,’ consultancy PwC states in its 2023 Mine SA report. ‘This presents several opportunities for South Africa that could reshape industries, diversify the economy and drive future prosperity. This will require additional investments, starting with more exploration, which in turn will depend on sensible regulation, available infrastructure and balanced tax regimes.

‘South Africa must use its metal resources to build strong partnerships across the value chain. The country must recognise that the most value is generated downstream in the energy mineral value chain. If we engage in the energy minerals value chain, we should prioritise sustainable production.’

Indeed, this potential is seeing some mining companies strategically positioning themselves for long-term growth by diversifying into critical minerals. Some have opted to alter their portfolios, either by expanding geographically or transitioning towards clean energy.

Of the more than 696 copper mines in operation globally, 127 are in South Africa, according to GlobalData’s mines and projects database. The five largest, by production in 2022, are the Palabora mine (owned by HBIS Group); Mogalakwena (Anglo American); Rustenburg Complex (Sibanye-Stillwater); Styldrift 1 (Royal Bafokeng Platinum); and Pilanesberg (Sedibelo Platinum Mines).

Another rising player is Copper 360, based in the Northern Cape. On track to become South Africa’s next major copper producer, it was established in late 2022 through a reverse takeover of Big Tree Copper and SHiP Copper, and produces high-quality copper with substantial cash margins. With a mining right encompassing 19 000 ha, the company oversees 12 copper mines (some with existing infrastructure) and 60 copper prospects equipped with advanced geological datasets. Projections suggest a life-of-mine exceeding 100 years across its operations.

Another significant producer is Orion Minerals’ Okiep copper project (OCP), also in the Northern Cape. In an August 2023 media statement, the company announced that ‘mineral resources at Flat Mine North, Flat Mine East and Flat Mine South now total 9.3 Mt at 1.3% Cu for 130 000 tons of contained copper, including a measured and indicated resource of 7.4 Mt at 1.4% Cu.

‘In addition to the previously announced mineral resource of 2.5 Mt at 1.4% Cu at Flat Mine (Nababeep), Jan Coetzee mine and Nababeep Kloof mine, this brings the total mineral resources within the Flat Mines area of the OCP to 12 Mt at 1.4% Cu for 160 000 tons of contained copper’.

The global transition to clean energy technologies has also placed a spotlight on nickel, which plays a pivotal role in enhancing the performance, lifespan and energy density of electric vehicles and energy storage solutions. Likewise, the stainless steel industry’s growth, which consumes approximately 70% of the global nickel supply, is projected to sustain the demand for the metal. GlobalData estimates that out of the 186 nickel mines in operation globally, South Africa is home to 127.

Among them is the Zeb Nickel project, located in South Africa’s Bushveld Complex – an area that holds more than 75% of the world’s platinum reserves and is commonly associated with magmatic nickel deposits. The project resides in the Ni-Cu-PGE producing zone of the Northern Limb, home to Anglo Platinum’s Mogalakwena mine, the largest open-cast platinum mine globally, situated less than 15 km north of the Zeb Nickel project.

South Africa is also the world’s largest producer of manganese ore by far, with reserves estimated at around at 640 million tons. A versatile mineral with extensive applications, manganese has experienced a marked upswing in local production and sales over the past decade.

The Northern Cape stands as the primary location for the majority of the country’s manganese deposits. In 2022, the manganese mining industry provided employment for more than 14 500 South Africans and contributed more than ZAR7 billion in tax revenue. This subsector also added some ZAR47 billion to foreign exchange reserves through export earnings that year.

Rare earth elements, meanwhile, are essential in various electronic devices (computers, TVs and smartphones), renewable energy technologies (wind turbines, solar panels and electric vehicle batteries) and national defence applications (jet engines, missile guidance systems, defence systems, satellites, GPS equipment and so on).

According to Brookings, in 2021, the global demand for rare earths soared to 125 000 tons, and projections estimate it will surge to 315 000 tons by 2030. ‘China has a dominant hold on the market – with 60% of global production and 85% of processing capacity,’ it states – adding, however, that countries are seeking to reduce their reliance on China as a source of production and processing.

‘This opens up a window of opportunity for African countries,’ it notes, highlighting South Africa’s Steenkampskraal mine, which has ‘one of the highest grades of rare earth elements in the world. It contains 15 elements and 86 900 tons of total rare earth oxides, with large deposits of neodymium and praseodymium’.

Another sector that rivals mining’s pivotal role in South Africa’s economic landscape is agriculture, serving as a cornerstone for both livelihoods and national development. It too contributes significantly to the country’s GDP, providing employment for a substantial portion of the population, particularly in rural areas. The diverse climate and geography of South Africa support a wide range of agricultural activities, from staple crops such as maize and wheat to the cultivation of fruits, vegetables and various livestock.

South Africa is a major exporter of agricultural products. According to Wandile Sihlobo, chief economist at the Agricultural Business Chamber of South Africa, the country’s agricultural exports amounted to US$3.9 billion in the third quarter of 2023, up by 4% year on year. ‘This quarter, the products that dominated the export list were citrus, maize, apples and pears, nuts, wine, soybeans, sugar and fruit juices,’ he writes in Agricultural Economics Today.

‘This solid export activity was both a function of improvement in volumes and prices, specifically of fruits. This more than offsets the effects of lower grains and oilseed prices, which have declined notably from their 2022 levels. Overall, South Africa’s agricultural exports amounted to US$10.2 billion in the first nine months of the year, up 1% from the same period in 2022.’

A recent report by the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation concurs that South Africa is poised to remain a net exporter of maize in the 2023/24 marketing year (May/April). ‘Maize exports are forecast at a well above-average level of 3.6 million tons in 2023/24, with a large proportion of this volume likely to be shipped to Asian countries, as in preceding years,’ it states. ‘Significant quantities are also foreseen to be exported to neighbouring Southern Africa countries that accounted for about 45% of the country’s total maize exports over the previous five marketing years.’

In addition to exports, the sector also fuels downstream industries such as agribusiness and processing.

Tourism, too, is an important sector of the South African economy, contributing to both revenue and employment. The country is host to a wide range of attractions, from iconic landmarks such as Table Mountain and Kruger National Park to historical sites, which draw both local and international visitors.

In recognising the strategic importance of tourism, the government is implementing initiatives to enhance infrastructure, promote sustainable tourism practices, and attract international visitors – and their efforts appear to be paying dividends. ‘International tourist arrivals from January to November 2023 totalled 7.6 million, representing a remarkable 51.8% increase when compared with the same period in 2022,’ according the national Department of Tourism. During the first 11 months of 2023, South Africa also hosted 5.8 million visitors from across the African continent, reflecting a substantial 75.5% of total arrivals. This figure demonstrates a notable increase compared to the corresponding period in 2022.

‘It is evident that our country remains attractive and that more can be unlocked with more policy and regulation revisions,’ says Patricia de Lille, Minister of Tourism. ‘I am committed to working with all partners and government colleagues to unlock barriers such as visa regulations, safety concerns and limited air access and air lift, so that we can grow our sector and meaningfully contribute to our country’s economy.’

South Africa is unquestionably a land rich with possibility, but collaboration between the public and private sectors is paramount to fostering an environment conducive to business growth, innovation and job creation. A shared commitment to inclusive development, promoting social equity and nurturing a culture of transparency will be essential components of a resilient and sustainable future.