Yttrium sounds like a winning word in a cryptic crossword puzzle. But if you paid attention in high school chemistry class, you’ll recognise it from the periodic table (Y, atomic number 39), where it sits near the string of neodymium (Nd, 60), samarium (Sm, 62), europium (Eu, 63), gadolinium (Gd, 64), terbium (TB, 65) and dysprosium (Dy, 66) – all of which are rare earth minerals, and all of which are now being mined near Phalaborwa and processed at Rainbow Rare Earths’ laboratory in Johannesburg.

In 2025, European cost, insurance and freight prices for yttrium oxide surged from around US$6/kg to between US$220/kg and US$320/kg (depending on pricing contract), driven by Chinese export controls, supply chain disruptions and market shortages.

According to Rainbow Rare Earths CEO George Bennett, it’s also an indication of the extent to which yttrium is used, with applications ranging from lasers and superconductors to LED TVs and cancer therapies.

Critical minerals – specifically the 17 rare earth elements – are ‘critical for both human and national security’, according to the Brookings Institution, which points to their use in electronics (computers, televisions and smartphones), renewable energy (wind turbines, solar panels and electric vehicle batteries) and national defence (jet engines, missile guidance and defence systems, satellites, GPS equipment and more).

This is where the conversation moves from the chemistry lab to the business economics class – especially for miners such as Rainbow Rare Earths.

‘The disruption and huge price increase for yttrium has once again highlighted the fragility of global dependence on China for strategic minerals, especially those like yttrium that are essential to high-tech and defence manufacturing,’ said Bennett.

‘Phalaborwa is a stand-out project in the rare earth space because it is a near-term and low-capital intensity source of all the economically and strategically important rare earths, including the heavies such as yttrium. This price increase positively impacts annual estimated EBITDA [earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation] for Phalaborwa, as there will be no extra cost to produce it as part of our proposed SEG+ product.’

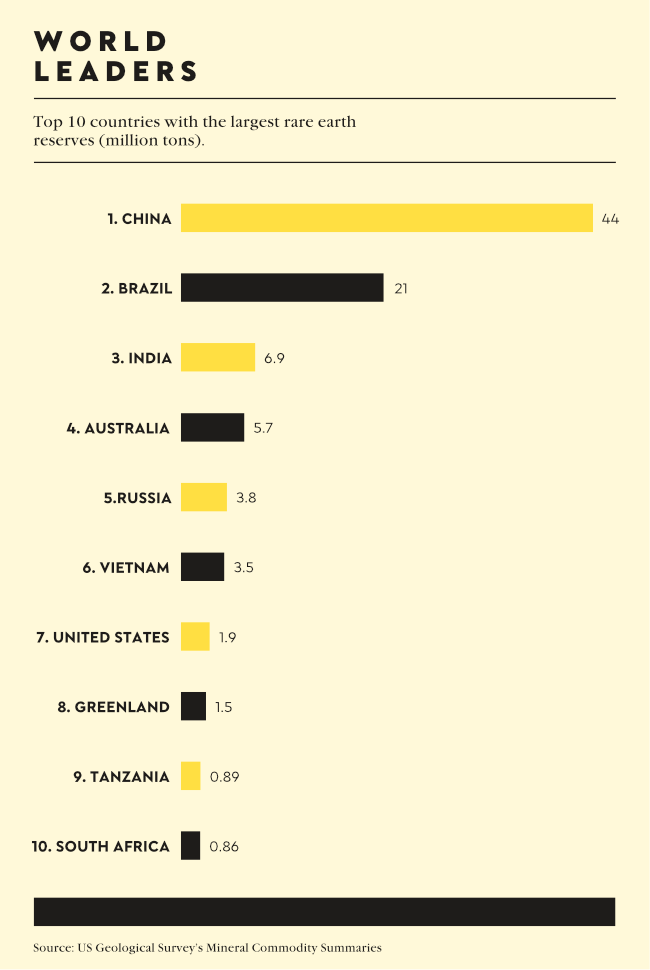

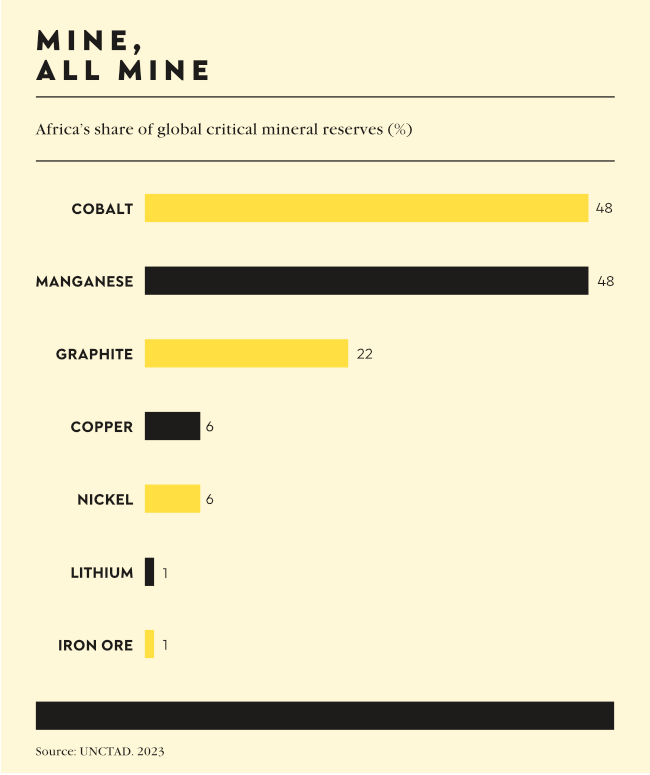

Rare earth minerals, in other words, are a growth sector – and Africa has a wealth of them. According to a recent report by the Atlantic Council’s Africa Centre, ‘the necessary resources for a low-carbon economy are abundant in Africa, with the continent possessing 30% of the world’s known mineral reserves – many of which are critical for the manufacturing of batteries, solar panels, wind turbines and other clean energy technologies. Africa’s untapped potential is greater yet, with research suggesting that the continent holds 85% of manganese reserves, 80% of platinum and chromium reserves, 47% of cobalt reserves and 21% of graphite reserves, much of which is unexplored or underexplored. Demand for these resources is also on the rise, expected to more than double between now and 2030’.

That 30% reserves figure is a rough estimate, as new deposits (such as the yttrium deposit in Phalaborwa) are being explored across the continent.

Africa’s rare earth minerals space has political considerations, placing the continent at the centre of an economic and diplomatic tug-of-war.

China currently dominates the global critical minerals value chain – and it has done so since 1987, when then premier Deng Xiaoping famously declared that ‘the Middle East has its oil, China has rare earths’. The Asian powerhouse now controls an estimated 92% of global rare earth minerals processing.

In October, a US State Department spokesperson told Fox News Digital that, ‘China’s dominance in global mineral supply chains – specifically in processing and refining – is a threat to both US and African interests. Beijing’s state-directed strategies exploit Africa’s natural resources, consolidate control over upstream mining assets, perpetuate opaque governance structures, degrade local environments and create economic dependencies that undermine regional stability’.

Talk like that puts places such as Steenkampskraal at the centre of global geopolitics and of the global economy. Steenkampskraal is a forgotten site in the Western Cape’s Knersvlakte, between blink-and-you’ll-miss-them villages such as Bitterfontein and Loeriesfontein. Anglo American mined monazite there in the 1950s but abandoned the mine, believing it was exhausted.

‘They were wrong – by about ZAR50 billion,’ Nik Eberl, the executive chair of the Future of Jobs Summit, writes in a recent opinion piece.

‘Steenkampskraal is among the highest-grade rare earth deposits on the planet – roughly 20% ore grade, compared with an industry average of 2%. In mining terms, that is the equivalent of finding a gold mine made of gold. South Africa, long seen as a supplier of traditional commodities, suddenly finds itself holding the keys to the technologies of the future.’

In late 2025, Steenkampskraal released the first tranche of funding required for the construction of its metallurgical phase from the Industrial Development Corporation, a state-owned entity.

‘This milestone marks a turning point in Steenkampskraal’s history to establish itself as a reliable global supplier of rare earth elements, essential for the technologies driving the green transition and advanced industries,’ said Enock Mathebula, the chair of Steenkampskraal Holdings.

‘Once operational, the plant will continually deliver a high-grade monazite concentrate containing more than 50% total rare earth oxides, positioning South Africa among the elite producers of critical minerals.’

Global demand for these minerals is expected to quadruple by 2030, amid accelerated demand for renewable energy and the production of the technologies needed to meet that demand. It’s a huge opportunity for South Africa, and for the continent as a whole.

‘Concurrently, eight major new mines are coming into operation in Angola, Malawi, South Africa and Tanzania,’ a recent In On Africa report noted. ‘All these mine operators say they will start production by 2029, and these eight operations alone will contribute 9% of the world’s supply of rare earth minerals. By 2030, the African continent is forecast to produce 10% of the world’s demand for these minerals, up from a negligible amount of less than 1% in 2020.’

The economic upside – shaped by geopolitical considerations as well – demands a clear strategy for how Africa will harness the potential of its rare earth and critical minerals.

‘These resources present the continent with a distinct opportunity to stimulate sustainable economic growth, create employment, and drive Africa’s re-industrialisation agenda,’ Gwede Mantashe, South African Minister of Mineral and Petroleum Resources, said at a partnership engagement ahead of November’s G20 Summit. ‘However, despite this abundance, the continent remains largely trapped in pit-to-port models, with limited beneficiation and minimal participation in global mining value chains. This historical pattern has left us contending with underdeveloped infrastructure and unequal access to downstream economic benefits, as supply chains remain concentrated in a few industrialised economies.’

With that in mind, South Africa announced a Critical Minerals and Metals Strategy in 2025. In line with that, it structured the G20 Critical Minerals Framework around six interrelated strategic pillars: mapping and exploration; governance and standards on economic, social and environmental aspects; investment, value addition and local development; stable, resilient and diversified value chains; innovation, circularity and technology; and skills, capacity and knowledge exchange.

One of the cornerstones of the G20 framework, Mantashe said, is ‘enabling mineral-endowed nations – such as ours – to move up the value chain by refining ores and producing value-added products closer to the point of production’.

The rare earth minerals space is experiencing – for want of a better term – a global gold rush. Prices are spiking by 5 000% (as happened to yttrium last year), while old mines are seeing new life as new deposits are unearthed (as has happened at Steenkampskraal). All of this comes as rival superpowers tussle over the world’s untapped – and undiscovered – critical minerals potential.