Deep-level hard-rock mining is a highly energy-intensive activity. Each of South Africa’s gold mines uses enough electricity to power a small city and the industry accounts for 15% of the country’s electricity consumption, a figure disproportionate to its much smaller contribution to the country’s GDP – about 8.3%.

However, energy supply to South Africa’s mining sector has been under great pressure for the past decade. This is literally a matter of life or death: the deepest mines (Mponeng and TauTona on Gauteng’s West Rand) reach about 3.9 km below the surface and the temperature at the rock face is above 60˚C – high enough to kill in about 30 minutes. This is why some three-fifths of electricity used by these mines drives enormous cooling and ventilation systems.

When, in January 2008, parastatal electricity supply company Eskom warned mining houses that it could not guarantee continuity of supply, the threat of blackouts effectively shut the industry down. It emphasised the need for mines in South Africa to implement off-grid backup solutions, something mining operations elsewhere on the continent had being doing for decades.

In South Africa, cost considerations have, since 2008, added weight to the imperative. In that year, Eskom instructed the mines, and other heavy electricity users, to cut consumption by 10% immediately. Usage has subsequently remained at lower levels, although costs have risen sharply. Once the cheapest in the world, Eskom’s tariffs have risen some 300% since 2009.

For Sibanye Gold, now South Africa’s biggest mining company in terms of employees, energy makes up 20% of operating costs, up from 9% in 2007 and despite a 15% drop in power consumption on a like-for-like basis over the 10-year period. Gold Fields spends 22% of its operating budget on electricity and AngloGold Ashanti about 20%.

As the mining industry cast around for energy solutions, South Africa’s renewables revolution was making rapid ground. Government began exploring the idea of renewable energy feed-in tariffs in 2009, largely in response to Eskom’s generation crisis. In 2011 it initiated the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement programme.

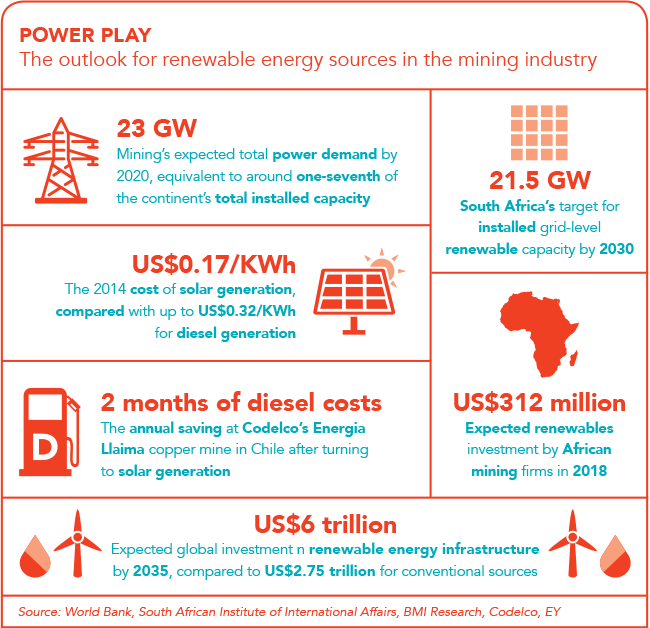

By mid-2016, 1 760 MW of wind- and solar-generating capacity was feeding into South Africa’s national grid and the cost, especially of solar generation, had fallen dramatically. The price of solar photovoltaic (PV) generation has dropped from ZAR2.75 per kWh in 2011 to an average of ZAR0.62 in 2016.

The synergy between renewables and mining in South Africa seemed obvious. But the industry is by nature conservative: too much is at risk – in terms of lives and investment – for most miners to easily accept a ‘radical’ new technology. Renewables have their limitations – solar and wind power require battery storage if they are to provide baseload electricity, but this pushes up the price.

In an East African case study, a solar plant produced electricity at a cost of US$0.22 to US$0.24 kWh (replacing diesel generators, which cost US$0.40 kWh). But when lithium battery storage was added to the system, the costs rose to US$0.58 kWh.

However, it seems that as the prices quoted fell, for PV electricity especially, so the case for incorporating renewables into the overall mix in mining became irresistible.

In South Africa, large solar PV projects are in implementation, notably by Sibanye Gold and subsequently Gold Fields. Sibanye has also begun investigating the integration of solar PV generation into its platinum operations in Rustenburg, recently taken ownership from Anglo American Platinum in November 2016.

Elsewhere on the continent, solar PV projects are being adopted in other hard-rock mining jurisdictions, notably Zambia’s copper fields and the Barrick-owned gold mines in northern Tanzania.

Gold Fields has implemented carbon-emission reduction and energy-savings projects at all six of its major gold mining assets in Australia, Ghana, Peru and South Africa. The company has targeted 20% renewable energy generation for all new mine developments. Its CEO Nick Holland was named ‘Visionary of the Year’ at the Renewables in Mining Conference in Toronto in November.

The company is in the process of installing a 40 MW solar PV plant at its sole South African asset, the highly automated South Deep mine on the Free State goldfields. Duncan Stevens, vice-president of group sustainable development at Gold Fields, argues that ‘there is a much stronger convergence between mining and renewables in South Africa now than ever before and we are also seeing this in other parts of the world’.

The South Deep solar project is intended not only to reduce carbon emissions but also to address ‘the rising costs of electricity and supply shortages in South Africa’.

South Deep’s request for proposals demonstrates one of the key attractions of solar solutions for the mining industry. The contractor is required to build, own and operate the solar power plant, which means there are no upfront costs for the gold mine. Gold Fields will sign a 20-year power purchase agreement, and the contractor will recover costs through selling electricity to the mine.

Also opting for solar PV on an even larger scale is Sibanye Gold. In May 2015, the company announced that it would be building a 150 MW solar PV plant on the West Rand. The plant is intended to provide 30% of Sibanye’s peak consumption and 10% of its overall needs. The first phase is due to come on-stream at the end of 2017.

Ben Potgieter, Sibanye’s head of engineering, argues that ‘solar PV generation will at least partly shield us from the worsening electricity security situation and the impact of load shedding’.

With international commodity prices in a two-year slump, electricity backup options have to make economic sense to miners. This often means integrating solar PV with diesel-generator sets, traditionally deployed on remote mine sites where electricity supply in unreliable. Diesel prices are currently low but the delivery of the fuel to mine site could pose a major problem.

These issues make solar PV an attractive option on the remote gold mines in northern Tanzania. From virtually nowhere in the 1980s, Tanzania has risen to become the continent’s fourth-largest gold producer, just behind Mali, after South Africa and Ghana. Some of Tanzania’s large mines – including AngloGold Ashanti’s Geita and Barrick’s Buzwagi – are open-pit operations where the major energy expenditures are diesel fuel for large earth-moving equipment. But Canadian miner Barrick, which owns its Tanzanian assets through a locally listed company called Acacia Mining, also has two major underground operations, Bulyanhulu and North Mara – and these require backup.

Barrick has undertaken renewables projects at its operations around the world. It built wind-turbine plants in Chile and Argentina but in Tanzania it originally focused on extending the national grid to North Mara, through a public-private partnership to which the mining company contributed US$28 million. That programme, initiated in 2007, has not been as successful as Barrick had hoped.

In fact, in 2015 a senior executive for Acacia complained that poor-quality grid supply was the company’s ‘biggest challenge’ on its mine sites in Tanzania. These included insufficient generation, a failure to upgrade transmission lines and distribution problems. Part of the solution is a 40 MW solar PV plant that is currently out on tender.

Zambia’s copper fields are another hard-rock mining jurisdiction that have been negatively affected by intermittent supply. The country has traditionally depended on hydroelectric power, which, in recent years, has been badly affected by drought. The country’s power deficit is 560 MW, most of which is imported.

Zambia recognises that it needs to diversify its energy mix, although for the government this means mostly coal-fired power stations. Certain mines have had to put up the shutters in the face of up to eight-hour power cuts daily.

However, in mid-2016, the Industrial Development Corporation of Zambia put out a tender for two 50 MW solar PV power plants. The best offer – US$0.06 per kWh – is a significantly lower price than miners pay for either grid or diesel electricity in Zambia. These developments are said to have excited the interest of big international players in Zambia’s copper industry. Renewables solutions providers are hoping that the industry will develop along the same lines as it has in South Africa, with new technology providing cost-competitive solutions to bottlenecks in the national grid.

Renewables are not the sole answer to the African mining industry’s energy security problems. But they are increasingly being factored into both on- and off-grid solutions, with the South African jurisdiction setting the example in both areas. The bottom line is that renewables, especially solar PV, are being found to be increasingly cost competitive.

It would be rash to suggest that for remote mines, the day of diesel is over. But it looks as if that old technology will have to share its space with renewables.